Official Journals By StatPerson Publication

|

Table of Content - Volume 7 Issue 1 -July2018

Comparison of effects of epidural fentanyl and dexmedetomidine on postoperative pain and gastrointestinal function following major abdominal surgeries

Vinayaka Jannu1, M G Dhorigol2*

1Assistant Professor, 2Professor, Department of Anaesthesiology, J N Medical College, Belagavi-590010, (S), Karnataka, INDIA. Email: drvinayakjannu84@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Acute postoperative pain control needs considerable attention and use of epidural opioids like fentanyl is associated with significant side effects like postoperative ileus. Dexmedetomidine, α2 receptor agonist has shown promising results of opioid sparing benefits. Objectives: To study was to compare the effect of epidural fentanyl and dexmedetomidine on postoperative pain and gastrointestinal function. Material and Methods: We conducted a prospective, randomized, double blind study on 60 adult patients undergoing major abdominal surgeries under general anaesthesia. Each patient received postoperative epidural analgesic regimens containing either of fentanyl or dexmedetomidine for 72 hours. VAS scores, requirement of rescue analgesics, nausea and vomiting, time to pass first flatus or faeces and other side effects were recorded. Data analysed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test, Wilcoxon signed rank sum test and Fisher’s exact test. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results: VAS pain scores were significantly lower for both the groups at rest, on coughing and on mobilisation for first 24hours following surgery. Dexmedetomidine group showed significantly lower scores (p < 0.05) on mobilisation after 24hours of postoperative period. Number of patients requesting additional rescue analgesic and total doses consumed are comparable between two groups for first 24hours of postoperative period. There were significant differences in the number of patients demanding antiemetic for the treatment of nausea and vomiting(p < 0.05). Time to first postoperative passage of flatus and defecation was significantly reduced in dexmedetomidine group(p < 0.05). The adverse effects such as sedation and pruritus were significantly higher in fentanyl group(p < 0.05). Conclusion: Epidural dexmedetomidine has superior analgesic profile and hastens the recovery of gastrointestinal function than epidural fentanyl in the postoperative period. Key Words: Epidural analgesia, Fentanyl, Dexmedetomidine, Postoperative ileus.

INTRODUCTION Acute postoperative pain following major upper abdominal surgeries needs considerable attention and is followed by sequelae such as organ dysfunction, prolonged convalescence and increased risk of morbidity. Despite advances in management, postoperative pain continues to be a challenge and can lead to detrimental physiological effects and psychosocial outcomes1. Among the most commonly used analgesic techniques, epidural local anaesthetic or local anaesthetic–opioid regimens are proved most effective in reducing surgical stress responses, autonomic reflexes and subsequently organ dysfunction; a substantial reduction in postoperative morbidity may be expected2,3. Postoperative ileus is a frequently observed complication following abdominal surgeries, presenting as the lack of flatus and defecation along with the inability to tolerate enteral nutrition. Prolonged ileus lasting for more than 5 days may result in increased morbidity and longer hospital stays, thus increased hospital costs4,5. Use of epidural opioids like fentanyl is associated with side effects such as sedation, pruritus, nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression and decreased gastrointestinal motility6,7. Dexmedetomidine is a selective α2 adrenoreceptor agonist showed beneficial effects on postoperative pain control8-10. In one previous study, epidural dexmedetomidine not only potentiated effects of local anaesthetics, but also shortened the time of first flatus of patients after nephrectomy11. We conducted a prospective, randomized trial to compare the effects of epidural fentanyl and dexmedetomidine on postoperative pain and gastrointestinal function following major abdominal surgeries. The two drugs were compared using parameters visual analogue scale, requirements of additional rescue analgesics, side effects related to analgesia and time to first postoperative flatus.

METHODS AND MATERIALS After obtaining approval of ethical committee, this prospective, randomized, double blind study was carried out on 60 adult patients (American Society of Anaesthesiologists[ASA] I and II) aged between 18 and 60 years, undergoing major abdominal surgeries under general anaesthesia. Exclusion criteria include haemodynamic instability, neurobehavioural disorders, history of chronic pain and contraindications for epidural catheter. Patients were allocated in a randomized manner by sealed envelope method into two groups, a) group F (fentanyl, n = 30) and b) group D (dexmedetomidine, n = 30). An informed and written consent was obtained from the patients during preanaesthetic check up one day prior to surgery. All patients were secured with 20G epidural catheter inserted using 18G Touhy needle at the T10 – T11 level and advanced 3cm inside the epidural space. Group F received a bolus of 15ml of fentanyl 2µg.ml-1 in 0.1% bupivacaine and group D received a bolus of dexmedetomidine 1µg.ml-1 in 0.1% bupivacaine. All patients were induced with intravenous (IV) thiopentone 5mg.kg-1, fentanyl2µg.kg-1 and atracurium 0.5mg.kg-1 and a tracheal tube was inserted. Anaesthesia was maintained using isoflurane in oxygen-air mixture. For all patients, hypotension was treated using isotonic normal saline, 6% hestarch or IV mephentermine 6mg incremental boluses to maintain systolic pressure above 90mmHg. At the end of first hour, all patients received continuous infusion of study drugs (group F, fentanyl 2µg.ml-1 and group D, dexmedetomidine 1µg.ml-1) in 0.1% bupivacaine at a rate of 5ml.hr-1. Preparation of study drugs and assessment of pain scores, side effects and gastrointestinal function are made by anaesthesiologists blinded to the study. For the first 72hours after surgery, all patients received 1g of IV paracetamol every 8hours. If additional analgesic was required, IV tramadol 1mg.kg-1 was administered. Patients were given IV ondansetron 4mg, if they demanded antiemetics. All patients were instructed preoperatively on the use of visual analogue scale (VAS), and to request supplementary analgesic and antiemetics if needed. Pain scores were assessed at 2,4, 8, 24, 32, 40, 48 and 72hours after surgery on a VAS(0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable) at rest, on coughing and on mobilisation from the supine to the sitting position. The number of tramadol doses were recorded. Nausea and vomiting was assessed on a scale of 0-3(0 = none, 1 = mild nausea on inquiry, 2 = moderate nausea/vomiting, treatment required, 3 = vomiting unresponsive to simple antiemetics). At all visits, gastrointestinal function was monitored by asking the patients if and when they had first passage of flatus and faeces. Other side effects like sedation, pruritus, respiratory depression and haemodynamic instability were recorded. Statistical Analysis: All values were reported as mean ± SD. Data analysis were performed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test for unpaired data, Wilcoxon signed rank sum test for paired data and Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. The analyses were made for three different VAS scores: at rest, on coughing and on mobilisation. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. RESULTS A total of 60 adult patients were included in the study, with 30 patients in each group. There were no significant differences between two groups for patient characteristics or operative data(Table 1). Table 1: Patient and perioperative data

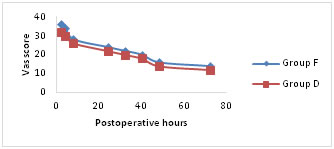

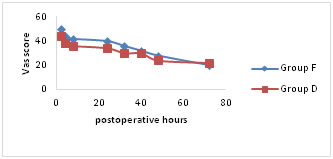

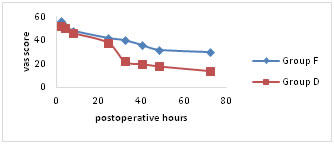

VAS pain scores were significantly lower for both the groups at rest, on coughing and on mobilisation for first 24hours following surgery (Fig a-c). Group D showed significantly lower scores (p < 0.05) on mobilisation after 24hours of postoperative period (Fig. c). Figure A

Figure B

Figure C Mean visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores (a) at rest, (b) on coughing and (c) during mobilisation from the supine to the sitting position. Number of patients requesting additional rescue analgesic and total doses of tramadol consumed are comparable between two groups for first 24 hours of postoperative period. Group D patients experienced significantly better (p < 0.05) epidural analgesia in comparison to group F. There were significant differences in the number of patients demanding antiemetic for the treatment of nausea and vomiting. The total doses of ondansetron used in group F are significantly higher (p < 0.05) in comparison to group D (Table 2).

Table 2:

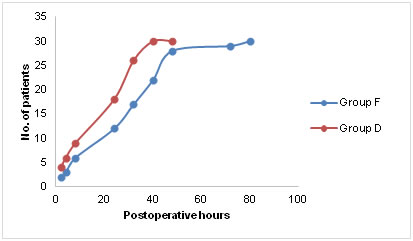

Number of patients and total doses of additional analgesic tramadol and antiemetic ondansetron among the two groups Time to first postoperative passage of flatus and defecation was significantly reduced in group D compared to group F (p < 0.05) as depicted in figure D. It was assumed that time to pass first flatus or fecus was not influenced by duration of surgery, extent of bowel handling and age of the patient.

Figure D

Time to first postoperative flatus or defecation in the postoperative period. The adverse effects such as sedation and pruritus were significantly higher in group F (p < 0.05). None of the enrolled patients suffered respiratory depression. Haemodynamic instability was observed in 6 patients of group D in the form of bradycardia and hypotension, which responded well to IV fluids and mephentermine (Table 3). Table 3:

Adverse effects: sedation, pruritus, respiratory depression and haemodynamic instability observed among study groups

DISCUSSION Major abdominal surgeries induce profound physiological responses in the postoperative period, characterized by increase in sympathoadrenal and other neuroendocrine activity and also increased cytokine production. Thoracic epidural analgesia has been shown to attenuate this stress response to surgery, improve the quality of postoperative analgesia in comparison to systemic opioids and hasten the recovery of gastrointestinal function2,6,7,11. The ideal epidural analgesic regimen must provide effective pain relief, with minimal side effects and high levels of patient satisfaction. The use of epidural opioids in combination with local anaesthetics was revolutionized by after discovery of opioid receptors in the dorsal horn of spinal cord that modulate nociceptive input12. A more lipophilic drug, such as fentanyl has been used safely via epidural route without the risk of respiratory depression, because of its rapid absorption into the spinal cord and nearby blood vessels decreasing the concentration in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Despite the initial enthusiasm of epidural opioids with their promise of excellent, long lasting analgesia, there is still considerable debate about their superiority over other epidural adjuvants in the postoperative period13. α2 adrenoreceptor agonists like dexmedetomidine are being extensively evaluated as an alternative with emphasis on opioid related side effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, pruritus and postoperative ileus8. The pharmacologic properties of dexmedetomidine have been studied and employed clinically to achieve desired effects in postoperative analgesic techniques14-16. High lipid solubility of dexmedetomidine allows rapid absorption into the CSF and binding to α2 receptors of spinal cord for its analgesic action. It enhances both central and peripheral neural blockade by local anaesthetics17. In this study, the quality of analgesia and overall patient satisfaction scores produced by epidural dexmedetomidine were comparable to fentanyl with fewer adverse effects such as nausea, pruritus, sedation and postoperative ileus. The need of rescue analgesics and antiemetics were significantly minimal in dexmedetomidine group. In preliminary investigations, a balanced anaesthesia with dexmedetomidine decreased the postoperative nausea and vomiting suggesting its potent antiemetic effect by its action on locus ceruleus18,19. The incidence ofbradycardia and hypotension was significantly higher with addition of dexmedetomidine20 and this was also apparent in the present study. Similar results were obtained in one previous study wherein 10µgms of epidural dexmedetomidine being more effective than 20µgms of fentanyl as an adjuvant to 0.5% ropivacaine10. The beneficiary effects of dexmedetomidine were attributed to its action on presynaptic and postsynaptic sympathetic nerve terminals and central nervous system thereby decreasing sympathetic outflow and norepinephrine release8. The pathophysiology of postoperative ileus is complex and involves many factors, including surgical trauma, activation of inhibitory sympathetic reflexes, use of opioids by acting on µ receptors of gastrointestinal tract, and induction of local and systemic inflammatory mediators21. Parasympathetic stimulation increases gastrointestinal motility, whereas sympathetic stimulation serves as the predominant inhibitory impetus to the bowel. The mechanisms by which dexmedetomidine improves bowel recovery may involve intra and postoperative sympatholysis and sparing of opioids use. Our study has few limitations. Instead of patient controlled epidural analgesia, fixed dose continuous epidural infusion of study drugs were used to avoid bias of variations of pain tolerance and patient demand of analgesics. Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting may be influenced by patient characteristics, pathophysiology of disease and complexity of surgical procedure. Lastly, duration of postoperative ileus may be affected by many causative factors including neurogenic, inflammatory and pharmacologic mechanisms. In summary, epidural dexmedetomidine demonstrated superior analgesic profile and hastened the recovery of gastrointestinal function than epidural fentanyl in the postoperative period.

REFERENCES

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home