Official Journals By StatPerson Publication

|

Table of Content - Volume 5 Issue 3 - March 2018

Evaluation of magnesium and calcium levels in obese adolescents

Sooraj Dev1, Sivaa Rajendran2*, Jyoti John3, Vasanthi Natarajan4

{1Post-graduate, 2Assistant Professor, 3Associate Professor, Department of Biochemistry} {4Associate Professor, Department of General Medicine} Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS), Pondicherry, INDIA. Email: drsivaar@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Overweight and obesity are the major risk factors for a number of chronic diseases including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and cancer etc. Obesity, in a mass population is usually assessed by measuring the Body mass index (BMI). Serum magnesium and calcium are involved in the various mechanisms behind the development of obesity. So we aimed to study the relationship of serum magnesium and calcium levels in obese individuals and non-obese controls. Materials and Methods: This study involved 50 obese and 50 non-obese individuals as cases and controls respectively. Serum magnesium and calcium were estimated colorimetrically for both the group by an automated analyzer. Results: The mean serum magnesium levels in cases and controls were 1.85± 0.35 mg/dL and 1.97 ±0.52 mg/dL respectively. Similarly the mean serum calcium levels in cases and controls were 8.41± 0.75 mg/dL and 9.67 ±0.78 mg/dL respectively. Both the parameters were lower in obese group than the non-obese group but the difference in the calcium levels alone showed statistical significance. Conclusion: In our study, we found lower levels of serum magnesium and calcium in obese individuals compared to non-obese individuals. Further studies on larger scale are needed to elucidate the role of magnesium and calcium in the pathogenesis of obesity. Key Words: Calcium, Magnesium, Obesity.

Obesity is a major health problem worldwide. According to world Health Organization (WHO) in 2008 about 1.4 billion adults were overweight globally.[1]Overweight and obesity are defined as, “abnormal, excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health”. Obesity, in a mass population is usually assessed by measuring the Body mass index (BMI).BMI of a person is calculated by dividing the weight of the person in kilograms by the square of his or her height in meters, i.e. BMI = Weight of person in kg/(height in meters)2 and its unit is kg/m2. Overweight and obesity are the major risk factors for a number of chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and cancer etc. Obesity was once considered a major health issue only in high income countries. Nevertheless, now it is dramatically on the rise in low and middle-income countries also, particularly in urban settings.2 As per the WHO criteria, to achieve optimum health, the median BMI for an adult population should be in the range of 21 to 23 kg/m2, while the goal for individuals should be to maintain BMI in the range of 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2. There is a mild risk of developing co-morbidities for BMI 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2and moderate to severe risk of co-morbidities for BMI greater than 30 kg/m2,3 In India, it was observed that the prevalence of obesity was similar in both men and women.[4]The etiological link between obesity and diseases is a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state which leads to complex pathological situations such as insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and oxidative stress etc. It is believed that overfeeding activates in all metabolically active cells leads to cytokine production and ultimately recruits immune cells in the extracellular environment inducing an overall systemic inflamation.5 This inflammatory response plays a critical role in the development of obesity related diseases.6,7 Various theories have been postulated to explain the development of obesity. It is a life style disease. It develops mainly due to over nutrition and physical inactivity, though genetic factors do play a role.8 Out of these theories metabolic alterations play a leading role. Since magnesium and calcium act as cofactors for various metabolic enzymes, any derangements in their levels may be associated with obesity.9 Total body magnesium is about 25 g, of which 60% is complexed with calcium in bone. Magnesium is important for the activation of many ATP requiring enzymes like hexokinase, fructokinase, phosphofructokinase, Adenylyl cyclase and C-AMP dependent kinases etc.10 In the human body, calcium is the fifth most common element and the most prevalent cation. Total calcium in the human body is about 1 to 1.5 kg, 99% of which is seen in bone and 1% in extracellular fluid.10 It is regulated by vitamin D, parathormone and calcitonin. Besides bone formation, its function is to regulate nerve and muscle function.11 It is also required as a co-factor for the activation of many enzymes like adenylylcyclase, glycogen phosphorylase etc. Many cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have confirmed effect of calcium on hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and obesity regulation etc.12 About 50% of the total calcium is found in bound form with albumin.[13]So albumin levels are important for measuring the corrected calcium/adjusted calcium levels. Serum magnesium and calcium are involved in the various mechanisms behind the development of obesity. Very few studies have been done relating the serum magnesium and calcium levels with obesity in Indian population so far. So we aimed to study the relationship of serum magnesium and calcium levels in obese individuals and non-obese controls. MATERIALS AND METHODS This case-control study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital which included 50 obese and 50 non-obese individuals who were in the age group of 21-40 years. Individuals with BMI were greater than 30 kg/m2 served as cases and those individuals with BMI <25 kg/m2 served as controls. Chronically ill patients, patients with CKD or endocrinal disorders, patients on regular medications or on steroids and those on calcium supplementations were excluded from the study. Serum magnesium was estimated Colorimetrically by Xylidyl blue method in an Fully automated chemistry analyzer.[14] The reference range is 1.6 -2.6mg/dL.[15]Serum calcium was estimated Colorimetrically by Arsenazo III method in an Fully automated chemistry analyzer.16 The reference range is 8.5-10.3 mg/dL.10 Since serum calcium levels are subjected to variations with the albumin levels correction was done for all the calcium levels by using the formula, Adjusted total calcium (mg/dL ) = Actual total calcium (mg/dL ) + 0.8 [ 4 – serum albumin (g/dL)]. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 17.0.Unpaired t-Test was used to compare the mean levels of magnesium and calcium in both groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

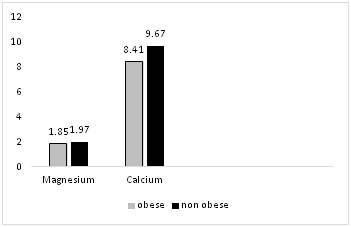

RESULTS Both the obese and the non-obese group included 25 males and 25 females to maintain gender equality. The mean age and BMI of participants in non-obese group were 33.6±5.2 years and 24±1.1 kg/m2 respectively. Similarly the mean age and BMI of participants in obese group were 34.6±5.5 years and 31±1.9 kg/m2 respectively. Out of the 50 obese individuals 48 were under class I obesity (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m2) and the remaining two were under class II obesity (BMI 35-39.9 kg/m2) The mean serum magnesium levels in cases and controls were 1.85± 0.35 mg/dL and 1.97 ±0.52 mg/dL respectively. Similarly the mean serum calcium levels in cases and controls were 8.41± 0.75 mg/dL and 9.67 ±0.78 mg/dL respectively.(Fig 1) Even though the mean levels of both magnesium and calcium are lower in obese group compared to that of the non-obese group, the difference is statistically significant for calcium levels only (Table 1).

Figure 1: Mean values (in mg/dL) of serum magnesium and calcium in obese and non-obese individuals

Table 1: Comparison of serum magnesium and calcium in obese and non-obese groups

*p-value < 0.05 statistically significant

DISCUSSION Our study included 50 obese individuals as cases and 50 non-obese individuals as controls. In our study, the mean levels of serum magnesium in the cases was 1.85 ± 0.35 mg/dL, while in controls was 1.97 ± 0.52 mg/dL.( Table 1) Thus the levels of magnesium were lower in the cases than the controls through the difference was not statistically significant may be because of the low sample size. This result was similar to so many previous other studies.17,18 Moreover about 18% of the cases were found to have very low magnesium levels in obese individuals as compared to controls. Magnesium is an important coenzyme for the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism and magnesium deficiency is known to be associated with glucose intolerance. Obesity is a condition in which there is high risk for glucose intolerance and insulin resistance leading further to dyslipidemia and coronary heart disease.[19]The lower magnesium levels in obese individuals could play an important role in the development of these disorders in obese individuals and may be involved in the pathogenesis of obesity itself. The mean levels of serum calcium in cases were 8.41 ± 0.75 mg/dL, lower than in controls where it was 9.67 ± 0.78 mg/dL. This difference is statistically highly significant p <0.001. (Table 1) There are some controversy regarding serum calcium levels in obese individuals. Some researchers have found higher serum calcium levels in obese individuals as compared to individuals with normal weight.20 There are some studies which found no significant difference between the levels of calcium in obese and normal weight.21 Our results are in accordance with the findings of Alba Gauseh et al, who found significantly lower levels of serum calcium in obese individuals as compared to healthy controls.22 Similar findings were reported by other authors who also observed lower levels of vitamin D and increased levels of PTH in obese individuals.22,23 Obesity is known to be associated with alterations in calcium metabolism.[24]Obese individuals who have higher BMI are more prone to vitamin D deficiency and increased PTH levels. But it is factual here that low circulating levels of vitamin D may be due to its sequestration in the excess adipose tissue in obese individuals that lowers the serum calcium levels.[25]Thus altered vitamin D status along with deranged calcium metabolism is seen in obese individuals.

CONCLUSION In our study, we found lower levels of serum magnesium and calcium in obese individuals compared to non-obese individuals. Further studies on larger scale are needed to elucidate the role of magnesium and calcium in the pathogenesis of obesity. REFERENCES

|

Home

Home