|

Table of Content Volume 12 Issue 1 - October 2019

Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and its clinical implications

Amrita Gupta

Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Varunarjun Medical College n Research Hospital, Shahjahanpur, UP, INDIA. Email:ag11677@gmail.com

Abstract Background: The human sacrum is a wedge shaped bone formed by fused five sacral vertebrae having four pairs of sacral foramina and forms the posterosuperior wall of the bony pelvis. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra (LSTV) is a congenital anomaly which involves either the sacralization of the lowest lumbar/first coccygeal vertebra or lumbarization of uppermost sacral vertebra. These vertebral bodies demonstrate varying morphology, ranging from broadened transverse processes to complete fusion. Material and method: This study was carried out on 98 dry human sacra (77 male and 21 female) from Department of Anatomy of SRMS-IMS, Bareilly, U.P. and Varunarjun Medical College, Shahjahanpur, U.P. Morphological study was done on the sacrum and classified as per Castellvi’s classification. Result: We highlight 17 cases of LSTV out of 98 sacrum. Out of 17, 12 sacrum showed complete sacralisation of 5th lumbar vertebrae, 3 sacrum showed complete lumbarisation of 1st sacral vertebrae and 2 sacrum showed simultaneous sacralisation of 1st coccygeal vertebrae and incomplete lumbarisation of 1st sacral vertebrae. Conclusion: Total incidence of LSTV was observed to be 17.3 % in the present study. Clinical Significance: The association of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) and low back pain, commonly referred to as Bertolotti’s syndrome, has a controversial history. To understand why defects in the lumbosacral region can lead to problems and sometimes intense pain, it is necessary to understand the biomechanics of a normal lumbar spine namely the functions it serves and the stresses it is subjected to. The genetic findings may have bioarcheological implications and may also be useful in forensic settings when trying to determine the identity or ancestry of an individual. Obstetricians, radiologists, anesthetists, neurologists and orthopedic surgeons must know about the existence of this variation to be able to correctly investigate, diagnose and treat the patients presenting with unusual signs and symptoms. Also the awareness of this possible congenital anomaly is important before any spinal surgery to avoid the incorrect numbering of vertebrae and consequently wrong level spinal surgery. Key words: Lumbosacral; Transitional; Vertebra; Low back pain.

INTRODUCTION Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) are congenital anomalies of the lumbosacral spine, involving lumbarization of 1st sacral vertebrae and sacralization, either of last lumbar or 1st coccygeal vertebrae. Its prevalence is 4- 30% in general population.1 The Lumbosacral spine is important for the following reasons:-

Low Back Pain in the presence of a LSTV is often referred to as Bertolotti’s syndrome.2 The major weight of the trunk when in the upright position is borne by skeletal structures. The lumbar spine experiences more stress from normal functions than any other part of the skeleton.2 To give support and bear the weight of the body, the integrity of all the vertebrae in the spine, especially in the lower back must be maintained. The failure of this integrity by any pathology, either congenital or acquired, will affect the stability of the spine and therefore its biomechanics. It is on this basis that LSTV are believed to be associated with increased liability for patients to develop various clinical complications.

MATERIAL AND METHODS The present study included an examination of 98 adult sacra (77 male and 21 female) available in the Department of Anatomy, SRMS-IMS, Bareilly and Varunarjun Medical College, Shahjahanpur, UP for the presence of LSTV. We classified them using Castellvi classification. Dry human sacra and human skeleton were studied for lumbosacral transition and numerical variations. Skeletal variations like Sacralization of L-5, lumbarization of S-1, number of sacral vertebra, shape of sacral hiatus and coccygeal fusion were also recorded. OBSERVATION AND RESULTS In the present study of 98 sacra, 77(78%) were male and 21(22%) were female. Only 17 (17.3%) showed Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebrae and 81 (82.7%) were normal sacra. Out of 77 male sacra, 11 (14.2%) and out of 21 female sacra, 6 (28.6%) were found to be Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebrae.

Table 1: showing incidence of Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebrae in the current study

Out of 17 LSTV, 12 sacrum showed complete sacralisation of 5th lumbar vertebrae, 2 sacrum showed simultaneous sacralisation of 1st coccygeal vertebrae and incomplete lumbarisation of 1st sacral vertebrae and 3 sacrum showed complete lumbarisation of 1st sacral vertebrae.

Table 2:Showing incidence of sacralisation, lumbarisation and fusion of coccyx in cases of LSTV

Out of total 17 Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebrae, 12 fall in Type III of Castellvi classification, all of which were bilateral (IIIb). 5 fall in Type IV (mixed) cateogory of Castellvi classification in which we found unilateral pseudarthrosis with the adjacent sacral ala on the left side and complete fusion with the adjacent sacral ala on the right side.

Table 3: showing incidence of types of LSTV

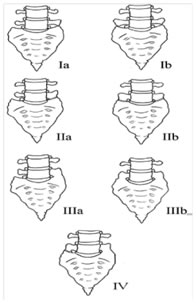

CLASSIFICATION OF LSTV ACCORDING TO CASTELLVI ET AL

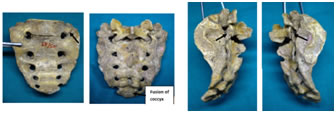

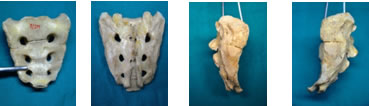

Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5 Figure 6 Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 9 Figure 10 Figure 11 Figure 12 Figure 1: Anterior view showing left sided dysplastic transverse process measuring 26 mm in width in sacralised transitional vertebrae; Figure 2: Photograph showing Posterior view of the sacralised transitional vertebra; Figure 3: Arrow showing complete fusion on Left Lateral surface of the sacralised transitional vertebra; Figure 4: Arrow showing complete fusion on Right Lateral surface of the sacralised transitional vertebra; Figure 5:Photograph showing Anterior view of the sacralised transitional vertebra (complete fusion); Figure 6: Photograph showing Posterior view of the transitional vertebra (complete fusion); Figure 7: Arrow showing complete fusion on Left Lateral surface; Figure 8: Arrow showing complete fusion on Right Lateral surface; Figure 9: Photograph showing Anterior view of the lumbralised transitional vertebra (3 ventral sacral foramina); Figure 10: Photograph showing Posterior view of the lumbralised transitional vertebra (3 dorsal sacral foramina); Figure 11: Arrow showing partial fusion on left lateral surface; Figure 12: Arrow showing partial fusion on Right lateral surface

DISCUSSION ur present study shows that the prevalence of LSTV is 17.3%. This finding is comparative with the prevalence reported by other observers.

Our finding agrees with the observations done by Vandana A et al (18.4%), Hald et al (14%) and Peh et al (13.2%). The present study shows that the frequency of sacralisation predominates than other types and also it is more common in males in comparison to females. The present study also states that majority cases of sacralization shows Type IIIb LSTV in which the enlarged transverse process is in complete bilateral fusion with adjacent sacral ala. PATHOGENESIS The occurrence of LSTV is linked to its embryological development and ossification defects. Vertebral column develops from the sclerotome of somites. Each sclerotome consists of loosely placed cells cranially and densely arranged cells caudally. Some densely packed cells migrate cranially opposite the centre of myotome where they form intervertebral disc. The remaining densely packed cells fuse with loosely arranged cells of the immediately caudal sclerotome to form the mesenchymal centrum, which develops into the vertebral body. Medial derivatives of sclerotome are vertebral body and intervertebral disc, while neural arches derive from the lateral regions of sclerotome3. Developmental defects occurring at the lumbosacral junction can result in transitional vertebrae that have characteristics of both lumbar and sacral vertebrae. That is, the morphology of the affected vertebra is intermediary or transitional with a combination of lumbar and sacral anatomical structures. The resulting characteristics produce a variety of morphological configurations collectively referred to as lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV). The developmental defects that result in LSTV are thought to be caused by delay in the timing threshold events occurring at the lumbosacral junction. This causes developmental fields to overlap or expand beyond normal, resulting in boundary shifts at the transitional areas of the vertebral column. Boundary shifts at the lumbosacral junction can occur caudally (lumbarization) or cranially (sacralization)4. Hox genes are among the major determinants of the morphological identity of the vertebrae. In addition, it has recently been described that some of the Hox genes play a global patterning role in vertebral development. When and how Hox genes determine somitic segmental identity is still an unresolved question. It is generally accepted that a specific combination of Hox genes expressed at a particular somitic level determines the axial identity of the resulting structures.5,6 LSTV may be accompanied by anomalies i.e. misshapen knee joint, modified parathyroid, thymus, cervical rib, the absence of teeth, a cleft secondary palate, supernumerary digits either in part or fully depending on mutation.7 Ossification defects are other potential cause of variation but both result in same morphology. BIOMECHANICS OF LUMBAR SPINE Transitional vertebrae are likely to affect the biomechanics of the lumbar spine. The lack of mobility at a fused transitional level or the decreased mobility at a partially fused or anomalously articulating vertebra lends stabilization to this level. This may be explained by the altered biomechanics from the anomalous joints between the LSTV and sacrum. First, there is restricted mobility between the transitional vertebra and sacrum due to the aberrant articulation and/or bony fusion8. The load can, thus, be effectively absorbed by the fused transverse process or the anomalous joint decreasing motion and relieving stress on the intervertebral disc. The increased stability between LSTV and the sacrum can potentially lead to hypermobility above the transitional segment, at the ipsilateral anomalous articulation and/or at the contralateral facet joint9. CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS The presence of LSTV associated with low back pain (LBP) is known as Bertolloti’s syndrome, is controversial and has been both supported and disputed since Bertolotti first described it in 1917. There are many reasons to believe that the presence of a transitional vertebra can lead to low back pain. Probable causes of low back pain include disc degeneration, disc prolapse, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, muscle strain or sprain, sacroiliac joint pain, chemical irritation, and nerve impingement; and the presence of a LSTV could potentially cause any of these. However, numerous studies have found no significant correlation between transitional vertebrae and low back pain,10,11 many other studies1,9 have found a significant correlation. Patients of LSTV have increase risk of disc bulge /prolapse/ herniation, slippage in lytic spondylolisthesis, low back pain from ipsilateral/ contralateral facet joint. It has been hypothesized that the lumbosacral transitional vertebra decreases the annulus fibrosus degeneration of the disc below, without having the same effect on endplates and nuclear complex 11. An association has been found between lumbosacral transitional vertebra and disc herniations as well as facet joint degeneration1. Otani et al stated that a lumbosacral transitional vertebra was reported more often in patients with disc herniation (17%) than in the control group (11%).12 It has been stated that the discs immediately above the transitional vertebra were significantly more degenerative compared with the disc between the transitional vertebra and the sacrum. Also, nerve root canal stenosis has been reported at the level suprajacent to the transitional vertebra.13 It has also been suggested that the lumbosacral transitional vertebra causes degenerative changes of the opposite facet joint. Luoma et al stated that because of the restriction of rotational and bending movements by the pseudarthroses, the L5-S1 disc is protected from traumatic events.11Castellviet al claimed that the transitional vertebrae causes abnormal torque movements above these anomalous structures, a fact that could result in disc degeneration.1Aihara et al in a study of 70 cadavers hypothesized that the iliolumbar ligament at the level immediately above the transitional vertebra is much thin and weak than in cadavers without a lumbosacral transitional vertebra. Particularly the posterior bands of the ligament at this level have the appearance of fascia rather than of a ligament. Due to that condition disc degeneration may occur at higher vertebral levels more frequently than level L5-S1. He also found the iliolumbar ligaments at the lumbosacral transitional vertebra consist of dense fibrous connective tissue, thus protecting the L5-S1 disc.14 It has been stated that the transitional vertebra should be kept in mind when low back pain appear especially in young individuals. Correct identification of an LSTV is essential because inaccurate identification can lead to surgical and procedural errors and formation of differential active motion segments. Symptoms can originate from the anomalous articulation itself, the contralateral facet joint (when unilateral), instability and early degeneration of the level cephalad to the transitional vertebrae, and nerve root compression from abnormal transverse process. The symptoms associated with each of the above processes are treated differently, requiring reliable techniques to not only identify LSTVs but also determine the type and site of the pathology generated by the transitional segment. In many sports, and golf in particular,15 the presence of LSTV places lumbar spine under significant unnatural stress that could potentially lead to Bertolotti syndrome. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra affects the position of the intercrestal line (Tuffier’s line) which corresponds to the level L4/L5 and is used as a landmark for needle insertion.16 Sacralization of fifth lumbar vertebra may cause greater difficulty during labour because of less mobile pelvis and it may results in low back pain problem. Malanga and Cook reported wrong level emergency decompression surgery, in a patient with cauda equina syndrome due to false assessment of complete lumbarization of S1.17 It supports the notion of a variant position of lumbosacral dermatomes.18 In forensic medicine, this anomaly can be very useful for identification of skeletal remains.19 During medicolegal investigations, some congenital abnormalities are of vital importance in identification, especially when antemortem records are available. A person with lumbosacral transitional vertebra is likely to seek medical advice if the condition is symptomatic and thus there is a high chance that antemortem medical records exist. From the medicolegal perspective, this has implications for the determination of primary indicators of identification. Thus, when skeletal remains are brought in for examination, the transitional vertebra can be helpful in confirming identity.20 CONCLUSION LSTV is a benign anatomical variation of the lumbosacral spine that is most frequently encountered by the spinal surgeon. The list of differential diagnosis should always include Bertolotti’s syndrome, when investigating back pain in young patients. Reviewing the literature makes it apparent that having a transitional vertebra does not necessitate symptoms, but those with a transitional vertebra who do get symptoms tend to have specific pathology. Though it has been long debated, there is convincing evidence of an association of low back pain with LSTV. Knowledge of the biomechanical alterations within the spine caused by LSTVs will aid the radiologist in understanding and recognizing the imaging findings seen in patients with low back pain and a transitional segment. Additionally, a thorough understanding of the importance for both accurate enumeration of LSTV and communication to the referring clinician will help to avoid such dreaded complications as wrong level spinal surgery. Furthermore, caution in numbering of lumbosacral vertebrae in symptomatic LSTV is of prime importance, especially if surgery is performed in the absence of regular plain radiographs.

REFERENCES

|

|

Home

Home