|

Table of Content - Volume 20 Issue 1 - October 2021

Rigid nasal endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of epistaxis

Joemol John1, Nishanth Savery2*, Mary Kurien3

1Assistant Professor, 2Associate Professor, Department of ENT, Sri Venkateshwaraa Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Puducherry, INDIA. 3Professor and HOD, Department of ENT, Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences, Puducherry, INDIA. Email: docnishuu@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Rigid nasal endoscopy, an integral part of nasal clinical evaluation, is also done in patients with epistaxis to identify the site of bleeding. This study was to evaluate the role of endoscopy in diagnosis and management of epistaxis. Methodology: Study included patients aged 12 years and above, who came to ENT or Emergency departments with epistaxis in 21 months period. They underwent rigid nasal endoscoy with 4 mm 0-degree Hopkins endoscope, in addition to other routine ENT and general physical examination in addition to relevant investigations. Results: There were 50 patients in this study with the majority of them (76%) being below 40 years of age. In 67% the site of bleeding was identified by routine ENT clinical examination, with nasal endoscopy accounting for additional 21%. In 18% patients, endoscopic assisted biopsy was done for mass lesions. Further investigations were done in 12% patients to identify aetiology of epistaxis. Endoscopy was deferred in 16% patients for immediate management as they had severe epistaxis. In majority of patients (84%) endoscopy was also done in immediate management of mild and moderate epistaxis for nasal packing or cauterisation of identifiable local site of bleeding. In severe epistaxis, endoscopy was used following elective pack removal for further management persistent epistaxis by sphenopalatine artery ligation or excision of local mass lesion. Conclusion: Nasal endoscopy has a major role in diagnosis and treatment of mild and moderate epistaxis, unlike in severe epistaxis where its role is limited to during its elective management. Key words: Diagnosis, Epistaxis, Nasal endoscopy, Management, Treatment

INTRODUCTION Epistaxis is defined as bleeding through the nose. It is the most frequent emergency in ENT presenting with prevalence about 10-12%.1 The sites of epistaxis are the Little’s area and the Woodruff’s plexus. Little’s area lies in the antero-inferior part of septum; a common site for anterior epistaxis in young children and adults whereas Woodruff’s plexus lies inferior to posterior end of inferior turbinate; gives rise to posterior epistaxis in adults.2 Local causes include idiopathic, trauma- nose pricking, facial injury, foreign body, inflammation, infection, allergic rhino sinusitis, nasal polyps, structural (septal spur or deviation), septal perforation, neoplasms and drugs. General causes are hypertension, haematological (coagulopathies, thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction), drugs- anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin), antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel), chronic kidney disease and chronic liver disease whereas congenital causes are unilateral choanal atresia, meningocele and glioma. Since the introduction of nasal endoscopy into the field of Otorhinolaryngology, the treatment paradigm for cases of severe epistaxis has shifted toward early and precise identification of the bleeding site.3 Nasal endoscopy takes an important role in evaluating epistaxis. It helps to reveal the hidden pathologies inside the nasal cavity which is not possible to detect by anterior rhinoscopy. Moreover, nasal endoscopy has advantage over posterior rhinoscopy as in most of the cases, due to excessive gag reflex, pathologies for posterior epistaxis remain undetected by conventional examination.4 As anterior and posterior rhinoscopy gives a restricted view of the nasal cavity, resulting in poor visualization of certain areas. The endoscope helps in visualising, what the naked eyes cannot for identifying and immediate control of bleeding. It helps in proper visualization and effective sealing of the point when seen by direct pressure for endoscopic nasal packing, endoscopic cautery or diathermy.5 Rigid nasal endoscope also helps in management by endoscopic mass resection, ligation of sphenopalatine artery and ligation of ethmoidal arteries. This study was conducted with an objective to identify the role of rigid nasal endoscopy in detecting the site and the hidden areas of epistaxis where anterior and posterior rhinoscopy failed.

METHODOLOGY This is a prospective descriptive study which included patients with epistaxis attending / referred to ENT OPD or emergency department from November 2014 to July 2016. It was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry. Following clearance from Institutional Research and Ethics Committees, with informed consent / with assent (patient and parent / guardian whenever indicated) the study was initiated. General physical and ENT examination, including anterior and posterior rhinoscopy was done. If epistaxis was not severe to override the latter and patient was stable, diagnostic nasal endoscopy was done under local anaesthesia. In those who the epistaxis was severe and nasal endoscopy not possible and/ or patients were clinically unstable, immediate nasal packing with emergency treatment was done and endoscopy done electively. Findings were documented. Nasal endoscopy was performed with 4 mm “0” degree Hopkins Telescope.

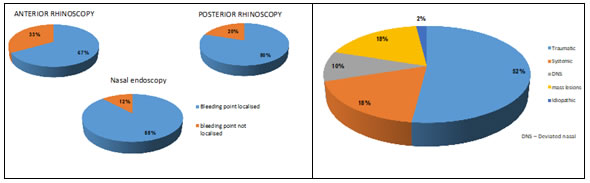

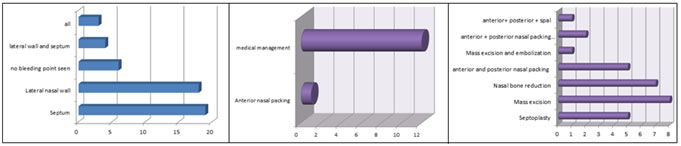

RESULTS The age group of the patients enrolled ranged from 12 to 60 years with the most common age group of 12-30 years of age predominantly males (80% - Table 1) and majority (52%) being among the 12-30 age group. In 54% (27) of patients, bleeding was insidious in onset, in 30% (15) it was sudden in onset and 16% (8) had continuous bleeding. Majority had mild or moderate (40% and 44% respectively) epistaxis with severe epistaxis in 16% patients (table 1). Diagnostic nasal endoscopy identified 88% of the bleeding points while clinical examination bleeding points was localised in 33% on anterior rhinoscopy and 88% with diagnostic nasal endoscopy. (Figure 1a, b, c) The most common site as diagnosed by nasal endoscopy was from the septum (50%) followed by from lateral nasal wall (44%), generalised in 6% with 12% no bleeding areas noted (Figure 3). Majority has surgical management of septoplasty, mass excision, nasal bone reduction, mass excision and embolization, anterior and posterior nasal packing, chemical cautery, anterior and posterior nasal packing with sphenopalatine artery cauterization (Figure 5) while 26% had conservative management of medication only (24%) with anterior nasal packing (2%) (Figure 4).

Table 1

Figure 1: Identification of bleeding area Figure 2: Diagnosis

Table 2: Details of diagnosis

Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5 Figure 3: SITE OF BLEEDING AS DIAGNOSED ON NASAL ENDOSCOPY Figure 4: CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT(26%) Figure 5: SURGICAL MANAGEMENT(74%)

DISCUSSION Epistaxis is a common problem which the otolaryngologist comes across and is alarming for the patient.6 The key to the management of epistaxis is to find the accurate bleeding site.7 The nasal endoscope is important for an otolaryngologist as it helps in proper visualization of the bleeding sites hidden to the naked eye to facilitate accurate management of bleeding areas which are difficult to assess.4, 8 In the present study done with 50 patients with epistaxis, anterior rhinoscopy and posterior rhinoscopy localized bleeding points in 33% and 20% patients respectively. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy, on the other hand, localized bleeding points in 88% patients, with 12% requiring additional investigations to identify the cause of epistaxis. This has been reported but authors have not quantified the percentage of those being identified by endoscopy.5,7 Among our patients with epistaxis, nasal endoscopy could be done in the emergency management of only those with mild and moderate epistaxis, while 16% patients had severe epistaxis, and nasal endoscopy was deferred in emergency setting, being done only in elective diagnostic procedures, once the severe bleeding was controlled with nasal packing. This has also mentioned by other authors though not quantified as well 5,8 However, this was reported by other authors as well. 5,6,7 Nasal endoscope is not superior to nasal packs as the first line of treatment in severe epistaxis. But with a fully equipped endoscopic set up and teamwork, severe epistaxis can also be easily treated.8 In our study, the cause of epistaxis in majority was traumatic (52%) including road traffic accident and traumatic ulcers followed by mass lesion, systemic illness, the least being deviated nasal septum with spur (10%). This is contrary to other reports where majority were hypertensives and alcoholics6 or due to posterior deviation nasal septum with ulcer, nasal mass lesion or bleeding points in lateral wall.8 Hypertensive epistaxis is difficult to manage.15 The reason behind hypertensive epistaxis could be due to poor blood pressure control. The need for regular blood pressure monitoring and the use of antihypertensive medications is to be emphasized.14 In these patients, though nasal packing temporarily controls bleeding, blood pressure needs to be under control for avoiding further epistaxis after pack removal. In elderly patients with hypertension, vascular wall changes occur due to fibrosis of arterial tunica media which leads to epistaxis.14 Alcohol intake is also a risk factor for severity of epistaxis as it reduces platelet aggregation and prolongs bleeding time.15 The local and systemic factors damage the nasal mucosa, affects vascular structures and disrupts blood clotting.16 18% patients in our study had nasal mass, for which biopsy was done to confirm the diagnosis. In an open labelled randomized controlled trial of 160 patients for comparison of precision and efficacy of emergency blind nasal packing with primary endoscopic control of epistaxis, 35% of those with blind nasal packing had post pack removal complication including nasal abrasions, synechiae and re-bleeding while those who had endoscopic packing had no complications.6 Endoscopic localization of the bleeding points facilitates treatment of the targeted area alone and avoids damage to the healthy mucosa which controls epistaxis early, reduces patients’ discomfort, hospital stay, thus being cost effective as well.12 Stankiewics in their study of nasal endoscopy and control of epistaxis reported that use of endoscope is useful in control of anterior and posterior epistaxis and has less morbidity than external procedures. Epistaxis in postoperative endoscopic sinus surgery and epistaxis secondary to tumours were easily treated using endoscopy. Using endoscope, patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia had more selective laser control. They concluded that endoscopic visualization and techniques were the state of art for the surgical control of epistaxis.17 Majority of the patients (74%), in our study underwent surgical management for control of epistaxis with only 13 patients underwent conservative management (28%) had medical management by using oxymetazoline or xylometazoline nasal drops and hypertensive patients (4%) underwent anterior nasal packing. The nasal endoscopy in the management of epistaxis has a major role in immediate management of mild and moderate epistaxis (as seen in 84%) and no role in immediate management of severe epistaxis (as seen in 16% patients).

CONCLUSION Nasal endoscopy has a major role in the diagnosis of epistaxis by identifying the site of bleeding even in the hidden areas of the nasal cavity, which are not visible to the naked eye and aids in the appropriate management of mild and moderate epistaxis, as the site of bleeding is precisely seen and can be managed by sealing the bleeding point with endoscopic guided pressure packing or cauterisation. Hence nasal endoscopy can be preferred as the first line of treatment in the management of epistaxis.

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

Home

Home