|

Table of Content - Volume 21 Issue 1 - January 2022

Comparative study of incidence of infective and non-infective causes of epistaxis in north Karnataka population

Syed Mushtaq1*, Ratkal Kedarnath2, Sanjeev C Tadasadmath3

1Associate Professor, 2Associate Professor, 3Professor & HOD, Department of ENT (Oto-Rhinolaryngology) Faculty of Medical Sciences Khaja Banda Nawaz University, Kalaburgi-585104, Karnataka, INDIA. Email: dr.smhashmi@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Epistaxis is the commonest Otorhinolarangological Emergency affecting up to 60% of the population in their life time but 6% requiring medical attention. Method: 85 (Eighty-Five) Epistaxic patients of different age groups treated conservatively after routine blood examination and serum electrolyte, urea, creatinine Urine routine examination, Blood group, coagulation profile. CT scan was done in selected cases to rule out neoplasm of the nose, PNS and nasopharynx. Moreover chest x-ray, ECG was performed for fitness procedure required for general Anaesthesia. Results: In the clinical manifestation, out of 85 cases 29 (34%) were non-infective (Idiopathic), 17 (20%) were trauma, 13 (15.2%) rhinitis, 2 (2.35%) tumour, 2 (2.35%) Iatrogenic, 3 (3.52%) foreign body, 2 (2.35%) blood dyscrasias, 1 (1.17%) congenital heart disease, 2 (2.35%) pregnancy. 29 (34%) epistaxis were non-infective, 56 (65.8%) were infected epistaxis, 34 (40%) were non-infective bleeding sites, 51 (60%) were infective bleeding sites. The frequency of complications was observed in non-infective (Idiopathic) epistaxis mainly. Conclusion: As the aetiology of epsitaxis broadly classified into local or systemic causes but it is difficult to classify properly hence 80-90% Epistaxis are considered idiopathic (non-infective) epistaxis. Trauma resulting from road traffic crush remains the most common etiological factor for epistaxis. Most cases were successfully managed with conservative (non-surgical) treatment alone such as nasal packing and local cauterization chemicals and Electro cauterization, under Endoscopic view wherever necessary. It is safe and cost effective. Surgery is the last resort to treat epistaxis. Key words: Rhinoscopy, DNE (Diagnostic Nasal Endoscopy), Conventional, Surgical, Abgel, Ribbon gauze

INTRODUCTION X Epistaxis term in which Epi means on and stazo means to fall in drops.1 Epistxis or nasal bleeding is one of the common otorhinolaryngolohgical emergencies worldwide and presents as challenge in resource poor centres where facilities are limited. Epistaxis is a problem frequently encountered in general practice and may present as an emergency, as a chronic problem of recurrent bleeds or may be a symptom of generalised disorder.2 It cannot affect the hemodynamic status but may cause great anxiety to patient and their relatives. Epistaxis is estimated to occur in 60% of persons globally during their life time and approximately 6% of those with nose bleeds seek medical treatment. The prevalence increased in children less than 10 years of age and then rises again after 35 years of age,3 generally males are slightly more effected than females. Epistaxis is commonly divided into anterior and posterior epistaxis depending upon the site of origin. Anterior nose bleeds arise from damage to keisselbachs plexus on the lower portion of anterior nasal septum known as the Little’s area where as posterior nose bleed; arises from damage to the posterior nasal septal artery. Anterior epistaxis is more common than posterior epistaxis accounting more than 70-80%.4 The aetiology of epistaxis can be broadly divided into local or systemic causes although even this distinction is difficult to make and the term Idiopathic Epistaxis (non-infective) is ultimately used in 80-90 cases.5 Hence attempt was made to rule out the systemic local or infective epistaxis and Idiopathic (non-infective) epistaxis patient. The results of this study will provide basis for planning of preventive strategies and establishment of treatment guide lines.

MATERIAL AND METHOD 85 patients aged between 10 to 60 years regularly visiting to ENT department of Khaja Banda Nawaz Teaching and General Hospital, Kalaburgi-585104, Karnataka were studied. Inclusive Criteria: All the patients presented the epistaxis were selected for study. Exclusion Criteria: Recent sinusoidal surgery, any bleeding diathesis or patients with earlier intervention on bleeding site, patients were excluded from study. Material and Method: Every patient underwent routine investigations, such as CBC, Hb% level, platelet count, RBS serum electrolyte, urea, creatinine, Urine routine examination and blood grouping, coagulation profile, such as prothrombin time, activated plasma thromboplastin time bleeding and clothing time was ruled out CT scan was done in selected cases to rule out neoplasm of the nose and paranasal sinuses and the naso-pharynx. Moreover, chest x-ray, ECG and serological test were performed for the fitness procedures requiring general anaesthesia, that is conventional posterior nasal packing and surgical methods to control epistaxis. Intravenous line was established in all patients with wide bore canula. Initially the patients were evaluated with anterior rhinoscopy to identify the site of bleeding patients who were brought to emergency room with complaint of recurrent episodes of excessive bleeding, underwent nasal endoscopic examination to search the site of bleeding which might have located more posteriorly. Treatment of the patients with epistaxis included conservative or non-surgical treatment and surgical or interventional treatment. Non-surgical treatment included application of topical vasoconstriction such as oxymetazoline and xylometazoline nasal drop, chemical and electrico cauterization of the bleeder and anterior and posterior nasal packing. Surgical methods were endoscopic electrocauterization of the bleeder and the SPA (spheno-palatine Artery) ligation. All the patients were initially treated conservatively and surgical treatment was considered only when conservative method failed to control the epistaxis, patients with bleeding disorders were packed with absorbable gelatine sponge (Abgel). The rest of the patients received conventional anterior nasal packing with ribbon gauze, posterior nasal packing was considered in the case of re-bleed in a patient who had anterior nasal pack in site. Surgical methods were the last resort to control bleeding in patients who had recurrent bleed or whose bleeding could not be controlled with those non-inventional methods. Duration of study was June 2016 to December 2021. Statistical analysis: Various clinical manifestations modalulities in epistaxis, bleeding sites, complications in both groups were classified with percentage. The statistical analysis was carried out in SPSS software. The ratio of the male and female was 2:1.

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS Table 1: Clinical manifestations of causes of Epistaxis – 29 (34.1%) were non-infective (Idiopathic), 17 (20%) traumatic, 13 (15.2%) Rhinitis (Inflammation), 14 (16.4%) HTN/Atherosclerosis, 2 (2.35%) tumours, 2 (2.35%) Iatrogenic, 3 (3.52%) foreign body, 2 (2.35%) Blood dyscrasis, 1 (1.17%) congenital heart disease, 2 (2.35%) pregnancy. Table 1: Clinical manifestations of causes of infective and non-infective causes of Epistaxis

Table 1: Clinical manifestations of causes of infective and non-infective causes of Epistaxis

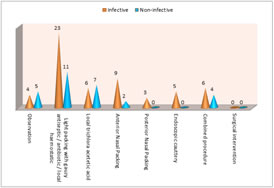

Table 2: Comparison modalities in infective and non-infective epistexis – In observation – 4 (4.70%) were infective and 5 (5.88%) were non-infective and total 9 (10.5%) were under observation. Light packing was done in 23 (27%) were infective, 11 (12.9%) were non-infective and total 34 (40%). Local trichlora acetetic acid method was used in 6 (%) infective, 7 (8.23%) non-infective epistaxis, total patients were 13 (15.2%). Anterior Nasal Packing was done in 9 (10.5%) infective, 2 (2.35%) non-infective epistaxis, total 11 (12.9%) treated with anterior nasal packing. Posterior Nasal packing was done in 3 (3.52%) only in infective epistaxis. Endoscopic cautery was done in 5 (5.88%) infective patients only. Combined procedure was done in 6 (7.05%) in infective, 4 (470%) non-infective, total 10 (11.7%) were treated with combined procedures. Table 2: Comparative study of Modalities in epistaxis

29 (34.1%) epistaxis patients were Non-infective, 56 (65.8%) were infected epistaxis (Idiopathic)

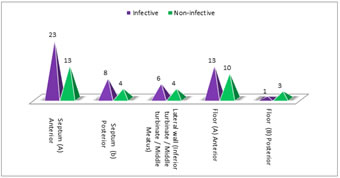

Table 2: Comparative study of Modalities in epistaxis Table 3: Comparison of bleeding sites in both infective and non-infective epistaxis. Septum – anterior had 28 (27%) infective and 13 (15.2%) non-infective bleedings sites. Septum posterior had 8 (9.4%) infective and 4 (4.7%) non-infective bleeding sites. Lateral wall of the Nose had 6 (7%) infective and 4 (4.7%) non-infective bleeding sites. Floor-anterior had 13 (15.2%) infective sites, 10 (11.7%) non-infective sites. Floor-posterior had 1 (1.17%) infective, 3 (3.5%) had non-infective bleeding sites.

Table 3: Comparison of bleeding sites in both infective and non-infection epistaxis

Out of 85 patients 34 (40%) were Non-infective 51 (60%) were infective bleeding sites.

Table 3: Comparison of bleeding sites in both infective and non-infection epistaxis

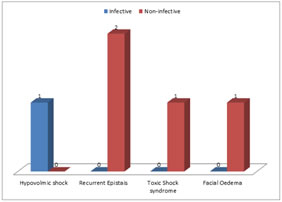

Table 4: Comparison of frequency of complications in both groups. Hypovalmic shock 1 (1.7%) in infective epistaxis patients. Recurrent epistaxis 2 (2.35%) in non-infective eptistaxis. Toxic shock syndrome 1 (1.7%) observed in non-infective epistaxis patients only. Facial oedema was observed 1 (1.7%) in non-infective epistaxis patients only. Table 4: Comparison of frequency of complications in both infective and non-infective epistaxis

Out of 5 (5.8%) 4 (4.70%) complications were observed in non-infective epistaxis

Table 4: Comparison of frequency of complications in both infective and non-infective epistaxis

DISCUSSION The present studies of comparison of infective and non-infective epistaxis in north Karnataka Population were studies. The clinical manifestation had 29 (34.1%) Non-infective (Idiopathic) epistaxis, 17 (20%) trauma, 13 (15.2%) rhinitis (inflammation), 14 (16.4%) HTN / atherosclerosis, 2 (2.35%) tumours, 2 (2.35%) Iatrogenic, 3 (3.32%) foreign body, 2 (2.35%) blood dyscrasis, 1 (1.17%) congenital heart disease, 2 (2.35%) pregnancy (Table-1). Comparison of modulation in epistaxis patients- The observation was 4 (4.70%) infective patients, 5 (5.88%) non-infective. In light packing with gauze 23 (27%) were infected, 11 (12.9%) were non-infected, Local trichloracetic acid 6 (7.05%) were infected, 7 (8.23%) were non-infected. In anterior nasal packing 9 (10.5%) infected, 2 (2.35%) non-infected. Posterior nasal package 3 (3.52%) was infective, Endoscopic cauttery 5 (5.88%) was infective, combined procedure 6 (7.05%) was infective 4 (4.70%) was non-infective (Idiopathic) (Table-2). In comparison of bleeding sites, 34 (40%) were non-infective (Idiopathic), 51 (60%) were infective bleeding sites (Table-3). Frequency of complications were 4 (4.70%) in non-infective or idiopathic and 1 (1.17%) in infective epistaxis (Table-1). These findings are more or less in agreement with previous studies.6,7,8 Most of the studies have included trauma, hypertension were Idiopathic (non-infective) group.9 Trauma being the major cause of epistaxis varied from minor injury such as digital trauma to varying degrees of nasal injury from road traffic injury. HTN (Hypertension) is the third commonest cause of epistaxis due to poor blood pressure control. It is also reported that epistaxis is the one of geriatric problem in older than 40 years of age.10 Hence it can be confirmed that, In old age there is lesser degree of immunity leads to cardio-vascular diseases like HTN / atherosclerosis, type-II DM, could be the major cause of epistaxis in old age above 40 years. Hence epistaxis above 40 years can be classified or considered as infective epistaxis because in old age minor traumatic injury to nose may result into severe degree of epistaxis. This epistaxis may be the diagnostic value of cerebro-vascular, cardio-vascular derangements. It is also noted that epistaxis observed in HTN indicated that the HTN is not controlled by anti HTN drugs hence there was epistaxis was noted in HTN patients11 or the HTN patients with epsitaxis might have essential Hypertension Under such scenario it is difficult to classify the infective or non-infective (Idiopathic) epistaxis. Management of epistaxis well is summarized by taking the preventive measures including face mask with shields gowns, hair coverage and double-gloving. The use of anti-microbial prophylaxis in the presence of nasal packing for the treatment of epistaxis remains controversial as it may lead to increased risk for sinusitis and toxic shock syndrome. Blood soaked pack and raw mucosal surface are good media for bacterial multiplication resulting in infection including sinusitis and sometimes toxic shock syndrome.12 The mortality rates associated with epistaxis were severe head injuries cardiac arrest, associated tension pneumothorax and nasopharyngeal cancer.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION The present study of comparison of infective and non-infective epistaxis there was 29% of idiopathic (non-infective) epistaxis, remaining appears to be infective though the aetiology was not clearly understood. Majority of espistaxis is managed with conservative methods and surgery remains to be last resort to treat epistaxis. This study demands further inventional study of embryological, genetic, nutritional patho-physiological studies because the factors and exact mechanism of epsitaxis is still un-clear. Limitation of Study: Owing to lack of latest technologies, less number of patients and tertiary location of present institution we have limited findings.

REFERENCE

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home