|

Table of Content - Volume 19 Issue 3- September 2021

Prospective study for classification of vertigo with special emphasis on BPPV

Yogesh Lakkas1*, Rameshwar A Warkad2, Uma Sundar3, Jitendra Rathod4, Rupali Kharat5

1,2Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, JIIU’S IIMSR Medical College, Warudi, Badnapur, Jalna – 431202, Maharashtra, INDIA. 3Professor, Department of Medicine, LTMMC, Sion, Mumbai, INDIA. 4Associate Professor, Department of ENT, MGM University, Aurangabad – 431005, INDIA. 5Medical officer, Department of Medicine, Endoworld Hospital, Aurangabad – 431005, INDIA. Email: yogeshlakkas@yahoo.co.in

Abstract Background: Vertigo is defined as an illusion of movement or disorientation in space. The movement is typically, but not invariably, a rotation in the horizontal plane. Vertigo is a common symptom of many varied conditions affecting the vestibular structures of the inner ear, the vestibular nerve, the vestibular nuclei in the brain stem, the cerebellum, the temporal cortex, and the blood and metabolic supply to these structures. The prevalence of vertigo rises with increasing age and ‘dizziness’ is the most common cause of presentation to the primary physician in people over 74 years old1. We carried out study in 73 patients. BPPV was found out to be the most common cause for the vertigo. There are various positioning maneuvers described in the literature, we evaluated Dix- Hallpike maneuver in detail as a very useful tool in diagnosis of BPPV in clinical practice. We did review other causes of vertigo and their significance in the studied patients. Study will definitely be helpful to general physicians and ENT specialist in their clinical practice. Key Word: classification of vertigo, BPPV.

INTRODUCTION Vertigo is defined as an illusion of movement or disorientation in space. The movement is typically, but not invariably, a rotation in the horizontal plane. Vertigo is a common symptom of many varied conditions affecting the vestibular structures of the inner ear, the vestibular nerve, the vestibular nuclei in the brain stem, the cerebellum, the temporal cortex, and the blood and metabolic supply to these structures. The prevalence of vertigo rises with increasing age and ‘dizziness’ is the most common cause of presentation to the primary physician in people over 74 years old1. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES The study aimed at evaluating etiopathogenesis of all acute and chronic cases of vertigo in OPD patients utilizing clinical data, provocative maneuvers and audiometry. It also evaluated natural course and associated features of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), and compared the same with migraine associated vertigo.

METHODOLOGY Data was collected over a period of 2 years in this prospective study. The sample comprised 73 patients of vertigo who were classified into central and peripheral causes. Audiogram was done in all patients. Imaging was performed if clinically indicated. Dix – Hallpike maneuver was used for the diagnosis of BPPV16-17. Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical purposes. Data classification and analysis was done using Microsoft Excel 2007. Ethical clearance to proceed with the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board. Patients recruited in the study were educated about the entity.

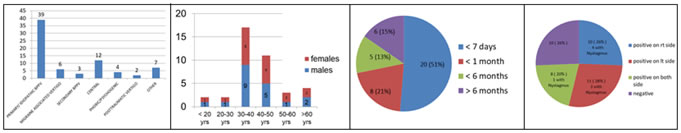

RESULTS Table 1 Table 2 Table 3 Table 4 Table 1: Classification of vertigo; Table 2: Age / Sex distribution in BPPV; Table 3: Duration of Presentation in BPPV; Table 4: Results of Dix - Hallpike maneuver in BPPV Table 5: Dix – Hallpike Test Results

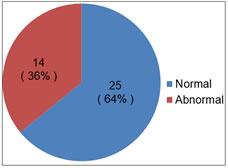

Table 5: Audiogram in BPPV

Table 7: Associated clinical features in BPPV

Table 8: Comparison between BPPV and migraine associated vertigo

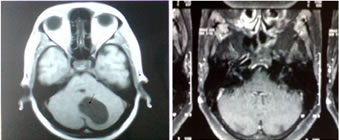

ILLUSTRATIVE MRIs FROM THE STUDY

Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 1: MRI showing posterior fossa tumor in a patient who presented as subacute onset vertigo; Figure 2: Contrast MRI showing inflamed 8th nerve in a case of vestibular neuritis.

DISCUSSION Among 73 patients, majority 39/73 (53.42%) were diagnosed as idiopathic BPPV based on history of positional vertigo and DH maneuver reproducing the symptoms.7,9,10 Secondary BPPV was diagnosed in 3/73 (4.10 %) patients. These patients also had h/o positional symptoms with the positive DH maneuver. They were diagnosed as vestibular neuronitis, labyrinthitis and post ear surgery (tympanoplasty). In vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis, the vertigo is of gradual onset, developing over several hours, followed by a sustained level of vertigo lasting days to weeks5,6. Among the patients diagnosed to have central vertigo 12/73 (16.43 %), causes included – 3 posterior circulation stroke, 5 MULTI-INFARCT states where vertigo was a predominant presenting symptom, 1sigmoid / transverse sinus thrombosis, 1 frontal space occupying lesion, 1 cerebellar space occupying lesion and 1 hippocampal sclerosis presented with vertigo as partial seizure. The description of vertigo in these patients was not significantly different although none had positional vertigo. In 4 patients with phobic /psychogenic vertigo, history was not typical of positional vertigo, and h/o stressors were present. 3 of them were diagnosed to have general anxiety disorder and 1 had MDD. 2 patients had post traumatic vertigo. 1 had non displaced squamous temporal bone # and the other one had lateral orbital wall #2,3. 6 patients had migraine associated vertigo8, 5/6 being female. These patients satisfied ICHD2 criteria for diagnosis of migraine. 4 of these 6 patients gave h/o positional vertigo. There were 7 patients with true vertigo which was not positional, and could not be classified into any of the above groups. 3 of them had diabetes mellitus, 2 had cervical spondylosis4, 1 had uncontrolled HTN on medication, and 1 had cyclic vomiting23-24. These factors could have been causative of the vertigo in these patients. Majority of our BPPV patients, 28/39 were in the group 30-50 years, equally distributed in males and females10. There were only 11 patients in the outlying age group. 51 % of our BPPV patients had acute presentation (< 1week). 49% had a more subacute / chronic history this bearing out the fact that BPPV is a relapsing – remitting kind of disorder, with spontaneous resolution taking months to occur.11,12 Also majority of the patients take vestibular sedative medication only without doing the corrective repositioning maneuvers, this contributes to the chronic course. Dix-Hallpike maneuver was used for diagnosis of BPPV16-17. 10/39 BPPV patients had DH maneuver positive on right side, it was positive on left side in 11 patients while 8 pts had DH maneuver positive on both sides. 10 patients had no positional symptoms at all on DH maneuver. A positive DH maneuver was concluded on the basis of reproducible vertigo on change of position with or without nystagmus9. A total of 8 patients (8/39) had nystagmus on DH Maneuver in addition to typical vertigo. In our study one patient had horizontal nystgamus s/o lateral canal BPPV. 10/39 patients in this study had no positional symptoms on the day of testing. These were still diagnosed to have BPPV on a typical h/o of positional vertigo which included vertigo on lying with neck extended or turning head to either side or vertigo on looking up13-15. They can be labeled to have “subjective BPPV”18-19. Among these 10 patients 6 had subacute presentation. And 5/6 were taking vestibular sedative on and off. Dix-Hallpike maneuver has sensitivity of 82 percent and specificity of 71 % for the in posterior canal BPPV. While positive predictive value for a positive Dix-Hallpike test is 83 percent and a negative predictive value is 52 percent for the diagnosis of BPPV20-21. 29 / 39 BPPV patients had positive DH maneuver. Among 34 non BPPV patients - 5/6 migraine associated vertigo, 2/3 secondary BPPV, 1/12 central vertigo, 1/2 post traumatic vertigo and 1/7 patients in the other “non specific“group had positive DH maneuver. 14/39 patients had an abnormal audiogram22, showing mild to moderate high frequency hearing loss. Average age in these patients was 40 years and mild hearing loss on audiogram can be age related. None had clinical hearing loss. A combination of hearing loss and vertigo would point to labyrynthitis which is usually characterized by higher frequency hearing loss but often profound and permanent. On comparison between BPPV and migraine associated vertigo notable feature in BPPV were h/o frequent headache in the past but not satisfying criteria for primary headache for migraine23-24. Lastly on comparison of BPPV patients with migraine associated vertigo, it was found that vomiting, h/o tinnitus, h/o motion sickness in the past was more commonly associated with migraine associated vertigo.11 DH maneuver was comparably positive in both the groups. Thus in the outpatient evaluation of vertigo, once general medical conditions (fluid loss, medication side effects, blood loss etc. )9 have been ruled out, one should evaluate for BPPV, migraine associated vertigo. This evaluation would include a good history, examination and relevant procedure such as Dix – Hallpike and Halmagyis maneuver. True vertigo may rarely be due to a posterior circulation ischemia and other CNS causes, such as cerebello - pontine angle tumors. A standard neurological examination should serve to detect these causes. Given the high prevalence of BPPV and migraine associated vertigo performance of diagnostic and canal repositioning maneuvers should be taught to general physicians routinely and regularly practiced in the OPD setting.

CONCLUSIONS

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home `

`