Official Journals By StatPerson Publication

|

Table of Content - Volume 4 Issue 1 - October 2017

Clinico radiological correlation with histopathological and molecular diagnosis in spinal tuberculosis

Monisha Kandala1, Sugnaneswar P2*, Veerapaneni Vaishnavi3, Venu Kandala4, Venkat Kishan T5, Pradeep Kiran6, Surabi Sushma7, Bhanu Teja7, Jaswanth Chowdary7, Aditya Vadan7, Praveena D7

1Biologist, The University of Texas, San Antonio, Texas, USA. {2Assistant Professor, Department of Orthopaedics} {4Professor and HOD, 6Senior Resident, 7Postgraduates, Department of Pulmonary Medicine} {5Assistant Professor, Department of Radiodiagnosis} Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences, Narketpally, INDIA. 3MBBS, JNMC, Belgaum, Karnataka, INDIA. Email: drgnaneswar@gmail.com

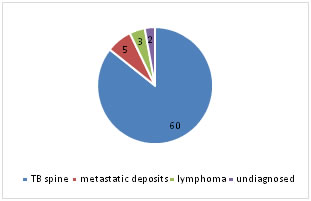

Abstract Background: Tuberculosis is a major global health problem particularly in the Indian sub- continent. Osteoarticular tuberculosis is seen in about 2-5% of all the cases. Spinal tuberculosis forms 50% of osteoarticular tuberculosis. Osteoarticular tuberculosis is difficult to diagnose because of deep seated lesions and being a paucibacillary disease results in delay in diagnosis and if undiagnosed stands a threat for dreaded complications like paraplegia and drug resistance. Therefore, quick and precise diagnosis is mandatory to initiate appropriate treatment to prevent serious complications. In this study we intended to correlate clinical, radiological diagnosis with histopathological and molecular diagnosis. Methods: We selected 70 cases of suspected spinal tuberculosis which were diagnosed clinically and radiologically byhistory, clinical examination, radiographs and MRI. These cases were subjected to histopathological examination and molecular diagnosis by Cartridge Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (CBNAAT) Results: The study included 70 cases of suspected spinal tuberculosis. Of which 60 cases were confirmed as spinal tuberculosis by histopathology and molecular diagnosis. histopathology alone could make diagnosis in 59 cases (98.33%)and molecular diagnosis in all the 60cases (100%). 10 cases were non tuberculous in etiology (metastatic deposits of carcinoma in 5 cases, lymphoma in 3 cases and 2 cases were undiagnosed) Conclusion: spinal tuberculosis is a paucibacillary disease difficult to diagnose. In this study HPE and molecular diagnosis gave quick and precise diagnosis. Culture takes longer time and negative culture can occur in partially treated cases. Molecular diagnosis is as good as culture but not a substitute. HPE and molecular diagnosis are complementary to each other. Key Words: Osteoarticular tuberculosis, spinal tuberculosis, molecular diagnosis, MRI.

About one third of the global population is infected with TB and HIV infection is prevalent in the same areas. India accounts for 21% of the global TB burden. 2-5% of all TB cases are osteoarticular of which 50% is constituted by spinal tuberculosis. Arrival of HIV infection has increased the incidence of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. spinal tuberculosis is difficult to diagnose because of paucibacillary disease and deep seated lesions. There is a need for quick and precise diagnosis to initiate early treatment and prevent dreaded complications like paraplegia. MATERIALS AND METHODS The study was conducted in KIMS tertiary care centre, narketpally between June 2015 and June 2017. After obtaining ethical committee approval, informed consent was taken from all patients. 70 cases of suspected spinal tuberculosis which are diagnosed clinically and radiologically (radiographs, MRI) were then subjected to CT guided biopsy and samples thus obtained were subjected to histopathological examination where the tissue was stained with Ziehl-Neelsen stain and was seen under the microscope for AFB and with hematoxylin and eosin stain to demonstrate epitheloid granuloma, langerhan’s cell with or without caseation. Tissue samples were also subjected to molecular diagnosis by CBNAAT.

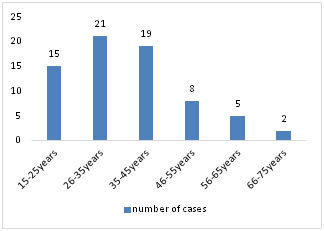

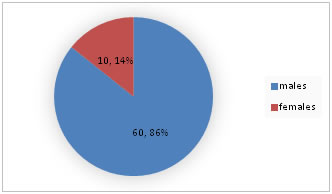

RESULTS Among 70 cases of suspected spinal tuberculosis included in the study, the age ranged from 15years to 75 years and their mean age was 32.5years. 55 out of 70 cases (78.5%) were under the age of 40 years. Out of 70 cases, 60(85.71%) were males and only 10 (14.28%) females.

Figure 1: Age distribution

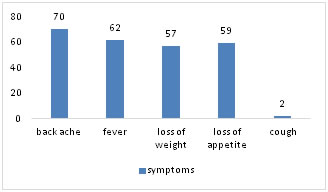

Figure 2: Sex distribution They had varied clinical presentation of which back ache was the most common symptom present in all the 70 cases (100%), fever in 62 patients (88.57%), loss of weight in 57 patients (81.42%), loss of appetite in 59 patients (84.28%) and cough only in two cases (2.85%) Table 1: Symptoms

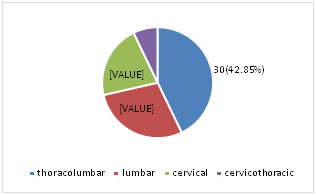

Figure 3: Symptoms Pain and tenderness over the spine was present in all the 70 cases (100%), gibbus was present in 47 cases (67.14%). Whereas paraplegia was present in one case and paraparesis in one case and chest radiograph features suggestive of tuberculosis was seen in two cases. Radiologically, thoracolumbar region was involved in 30cases (42.85%), lumbar region in 20 cases (28.57%), cervical in 15 cases (21.42%) and cervicothoracic in 5 cases (7.14%). Table 2: Region of spine affected

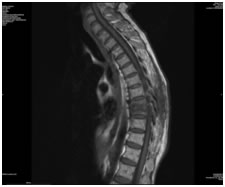

Figure 4:

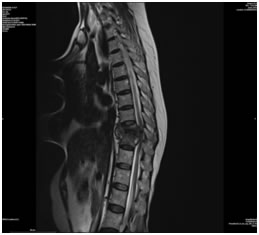

Figure 5: Sagittal T1 weighted MR image showing low signal intensity in disc and vertebral end plates Figure 6: Sagittal T2 weighted MR images showing heterogenous signal intensity noted involving vertebral end plates and disc at T10-T11 with epidural collection causing mild cord compression Out of 70 cases, fifty nine cases (84.2%) had typical histopathological changes suggestive of tuberculosis of the spine was found. Histopathology showed epitheloid cells, Langerhans type of giant cells and round cell infiltration. 10 cases (14.28%) showed non tuberculous diagnosis. Five of these cases had metastatic deposits and three cases had lymphoma and in two cases diagnosis could not be established due to inadequate tissue sample.

Figure 7: Histopathological diagnosis Molecular diagnosis has confirmed the tuberculous etiology in all the 60 cases (85.71%). 60 Patients who were diagnosed clinically, radiologically as spinal tuberculosis were confirmed by histopathology in 59 cases (98.33%) and molecular diagnosis was made in all the 60 cases(100%).Overall diagnosis could be established in all the cases. Where histopathology could not establish the diagnosis, molecular diagnosis confirmed the tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION Tuberculosis is one of the most ancient disease known to mankind. One of the Earliest evidence of spinal tuberculosis noted in the Egyptian Mummies dates back to around 3000BC1. It is now a global pandemic affecting mostly the developing countries. In 2015, approximately 10.4 million new cases of tuberculosis have been reported worldwide2. The risk of developing tuberculosis is estimated to be 20-37 times greater in people co-infected with HIV infection3. The exact incidence and prevalence of spinal TB is not known. In countries with higher burden of TB, osteoarticular tuberculosis accounts for 10-15% of all the tuberculosis cases. Approximately 10% of patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis have skeletal involvement. Spinal TB accounts for 50% of osteoarticular TB4. Among 70 cases of suspected spinal tuberculosis cases included in the study, the age group ranged from 15-75years with a mean of 32.5 years. 55 (78.57%) out of 70 cases were under the age of 40years suggesting that TB spine is also more common among young individuals. Konstam and Blesovsky5 and Tuli6 and Sadik I Shaik7 also noted that over 50% of their cases were seen in the first three decades of life. The predilection for younger patients to develop spinal TB was noted in the present study too. The disease is equally distributed among both sexes8 but Similar to a study by Chang-Hua Chen that showed a male preponderance (53%) of spinal tuberculosis9 and Alam et al whose study revealed a male preponderance in the ratio of 1.63:110, our study too showed a male preponderance noted as high as 85.71% which may be attributed to increased exposure to mycobacteria and easier access to health care system by males which may be only an apparent increase of disease among males. Chronic back ache has been the most common symptom in spinal tuberculosis collectively including our series where the back ache was the predominant complaint seen in all the 70 patients (100%). BMGD Yasaratne et al in their study have demonstrated the incidence of back ache in 91% of their patients11. In our study, back ache was followed by other symptoms of fever in 62 cases (88.57%), loss of appetite in 59 cases (84.28%), loss of weight in 57 cases (81.42%) and cough only in two cases (2.85%) For radioluscent lesions (osteoporosis) to be visible on the plain radiographs, there must be a 30% bone mineral loss12-14. Therefore, imaging modalities like CT and MRI offer advantage in delineating the lesions and their extensions in a better way thereby aiding in the early diagnosis. MRI is a more sensitive and specific imaging technique than Computerised Tomography and radiographs with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 88% in the diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis15-17. The earliest radiological findings include loss of definition of plate margins with destruction of vertebral body, loss of disk height, erosion of end plates. Calcification of paraspinal cold abscess is highly suggestive of tuberculosis18-20.MRI enables determination of the mechanism for neurological involvement (meningomyelitis) by demonstrating disc collapse/destruction, cold abscess, vertebral wedging/ collapse, marrow edema and spinal deformities17,21-24.In our study, thoracolumbar region was the most commonly affected region accounting to 30 cases (42.85%) similar to studies by Tuli6 and Shaik7 and BMGD Yasaratne11 as well followed by lumbar region in 20 cases(28.57%). In our study, Chest radiographs showed cavitary lesions in two patients who complained of cough which accounted for 2.85% of all the cases and tested positive for AFB on sputum direct smear examination. This is in contrast to findings by Nussbaum et al who in their series of 29 patients of spinal tuberculosis in United States noted concurrent pulmonary tuberculosis in around 10% of their cases25. Even though it is agreed that CT, MRI have definite advantage over conventional radiographs but they may not always differentiate various types of spinal infections from one another and also from neoplasms7. Thus, histopathological examination plays a vital role in the diagnosis of Potts spine and also other forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis but sometimes it may be inconclusive and may mimic other diseases and in addition requires high expertise. The current study diagnosed 10 non tuberculous conditions which were diagnosed to be neoplastic by histopathological examination (5 cases of metastatic deposits, 3 cases of lymphoma and in 2 cases diagnosis could not be established due to inadequate sample of tissue.) therefore, there is a need for multipronged approach for the diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis. The studies have quoted detection rate of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by histopathological examination including Potts spine varying from 72-97%26,27. In our study, 60 cases of spinal tuberculosis were diagnosed. The histopathological diagnosis of tuberculosis could be made in 59 cases out of total 70 cases (84.29%) and among 60 cases of diagnosed spinal tuberculosis, histopathological diagnosis could be established in 59 cases(98.33%). The histopathological diagnosis were confirmed either by the presence of AFB or histopathological changes strongly suggestive of tuberculosis (epitheloid cells, langerhan cells and round cell infiltration). The histopathological positivity in our series was 98.33%. Early diagnosis and treatment of spinal TB is essential to prevent dreaded complications like neurological deficit. The “gold standard” for diagnosis is isolation and culture of tuberculous bacilli. However, culture methods are slow and insensitive especially in cases of paucibacillary skeletal lesions and might yield no growth in partially treated cases6,28. The shortcomings of these methods led to the development of more sensitive and rapid detection methods like CBNAAT (cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test) or Gene Xpert which represent a major advance in the diagnosis of tuberculosis which have shown to have higher efficiency in the diagnosis of pulmonary as well as extrapulmonary tuberculosis. A study by M Held, M Laubscher et al showed a sensitivity of 95.6%, specificity of 96.2%, positive predictive value of 97.7% and negative predictive value of 92.6%29. Out of 70 cases included in the study, CBNAAT was tested positive in 60 cases (85.71%) and in all the 60 cases of tuberculous lesions it tested positive (100%). one of the disadvantages of CBNAAT is that in contrast to culture, it gives a false positive result in non viable bacilli30. In such circumstances, active TB has to be confirmed clinically and by means of variable imaging modalities. Molecular diagnosis for tuberculosis was positive in 100% cases in our series. Where histopathological examination did not yield the diagnosis, was confirmed by molecular test.

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

|

|

Home

Home