|

Table of Content - Volume 19 Issue 3 - September 2021

Performance of schizophrenia patients on self-monitoring task: A cross-sectional study

Sai Krishna Tikka1, Namdev Chawan2*, S Haque Nizamie3, Archana Kumari Das4, Nidhi Agarwal5

1Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, Hyderabad, INDIA. 2Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Mahadevappa Rampure Medical College, Gulbarga, INDIA. 3Retired Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Ex-Director, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, INDIA. 4Department of Clinical, Department of Psychology, Ranchi Institute of Neuro-Psychiatry and Allied Sciences, Ranchi 5Clinical Psychologist, Christian Medical College, Ludhiana, INDIA. Email: namdevjr@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Self-disorders are fairly common in schizophrenia patients. They are hypothesized to be due to self-monitoring deficits, which may be related to other schizophrenia symptoms too. We conducted a cross sectional study primarily to compare performance of schizophrenia patients on a self-monitoring task with healthy controls. The secondary aim of the study was to assess the relationship between the performance on the self-monitoring task and schizophrenia psychopathology. We compared 40 schizophrenia patients with 20 healthy controls. A drawing test to assess self-monitoring was used. On the self-monitoring test, schizophrenia patients scored significantly lower than the healthy controls; the significance was retained even after controlling for difference in recognition memory scores. A significant negative correlation was found between the self-monitoring scores and the PANSS positive symptom score. We conclude that schizophrenia patients show significant deficits in self-monitoring, which might be responsible not only for self-disorders, but also other positive symptoms, in general. Keywords: schizophrenia; self-monitoring; positive symptoms; interoception; drawing test.

INTRODUCTION Conscious living as- one, single, defined unit of experience and action, in time has been conceptualized as ‘self’.1 This construct refers to the personal attribution of “mineness,” “myness,” “for-me-ness,” or “ipseity”.2 Schizophrenia patients have been found to be characteristically deficient in the sense of “ipseity” of the field of awareness.3 Historically, phenomenological research suggests that this deficiency may be a core marker of schizophrenia. While Emil Kraepelin regarded “disunity of consciousness” a fundamental feature, Eugen Bleuler considered experiential “ego disorders” among the pathognomonic symptoms; and Karl Jaspers described the sense of “self-presence” being fundamentally weakened in schizophrenia patients.4 Most importantly, Kurt Schneider’s first-rank symptoms (FRS) that form a basis for current day’s categorical nomenclature of schizophrenia underpin a consideration that self-awareness undergoes radical change in patients with schizophrenia.5 Although substantial amount of phenomenological research highlights the ‘self’ perspective, interest in empirical biological research in this context is relatively new yet sparse. Predictably, schizophrenia patients have been found to have impairments in self-monitoring and have been conceptualized as having an underlying defective “self-internal monitoring system”.6-7 The primary aim of the index study was to compare performance on a self-monitoring task between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. The secondary aim of the study was to assess the relationship between the performance on the self-monitoring task and schizophrenia psychopathology.

METHODS Sample and clinical tools The data was retrieved from a project titled “transcranial magnetic stimulation in modulating neurodevelopmental factors in schizophrenia” (performance on the self-monitoring task was one of the secondary outcome variables) that was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of a tertiary care mental-health institute in Eastern India. A written informed consent was taken from all the participants (and their legally qualified representatives in case of patients) before enrolling them for the study. Data of a total of 40 patients and 20 healthy controls was retrieved. Purposive sampling method was used for enrolling subjects from various inpatient wards of the institute. Male patients aged 18–50 years, all right handed, were included. Diagnosis of schizophrenia was made according to the ICD-10 DCR8 criteria. All patients were on a stable dose of antipsychotic medications. Severity of psychopathology in schizophrenia patients was evaluated by administering the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).9 These patients were recruited from the in-patient wards of the hospital. A sample selected from the hospital staff and community living in the vicinity of the institute were included as ‘healthy controls’; they were age, gender and education matched to the patient group. Additionally, the healthy controls were screened with General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-1210 and only those with scores less than three were included. The exclusion criteria for both the groups were: other comorbid psychiatric disorders, history of neurological illness or significant head injury or significant medical disorders (i.e. uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, cancers, etc). Patients with comorbid substance dependence (excluding nicotine and caffeine) were also excluded. Self-monitoring task Self-monitoring was assessed based on an adaptation from the series of drawing tests given by Stirling et al. (2001).11 In this test, there are two drawing tests. Drawing test 1 taps self-monitoring mechanisms, whereas drawing test 2 is a control test that primarily assesses recognition memory. Steps of the task are:

Correct identification was scored ‘1’ and incorrect ‘0’. Two scores (one each for test 1 and test 2) were generated (range: 0-8). Statistical analysis Group differences for the continuous and categorical variables were computed using independent samples t test and Pearson chi square test (or Fisher’s exact test wherever applicable), respectively. Comparison of self-monitoring task between the two groups was done using the, serum BDNF levels and MPAs between the groups was done using independent samples ‘t’ test. A supplementary ANCOVA (analysis for covariance) was also performed to test to control for the influence of recognition memory on self-monitoring. A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between self-monitoring scores and the PANSS scores, age and duration of illness. The level of significance was kept at .05. Statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

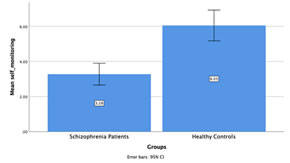

RESULTS Table below shows the comparison of socio-demographic variables between the two groups and clinical characteristics of the patient group. The two groups were comparable on all variables except employment. Significantly higher healthy controls were employed than the patients. The mean duration of illness for patients was >4 years. On the self-monitoring test (drawing test 1), schizophrenia patients (3.28±1.93) scored significantly lower (t=5.29; p<.001) than the healthy controls (6.05±1.88). See figure below. On the recognition memory test (drawing test 2) too, schizophrenia patients (6.40±1.46) scored significantly lower (t=4.51;p<.001) than the health controls (7.90±0.31). However, no confounding effect of recognition memory on the comparison of self-monitoring between the groups was seen (F=2.92;p=.09). After correcting for the difference in recognition memory (using ANCOVA), the difference on the performance on the self-monitoring task between the two groups remained significant (F=6.05;p<.001). On the correlation analysis, a significant negative correlation was found between the self-monitoring scores and the PANSS positive symptom score (r=-.428;p=.006). No other significant correlations were noted. Table 1: Comparison of socio demographic and clinical variables between the groups

Figure 1: Comparison of performance on self-monitoring task between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls

DISCUSSION The last two decades has seen a rise in the research interest on understanding self-deficits in schizophrenia patients. The focus has been on experimental psychology for studying these deficits. Our study shows that, indeed, there are gross deficits in self-monitoring in patients with schizophrenia. The self-disturbances in schizophrenia have been conceptualized to be due to two processes– hyper reflexivity and diminished self-affection. Hyper reflexivity is a puzzled state characterized by hyperalert monitoring and subsequently qualitative changes of inner life inner processes such as thinking, perceiving or motion. Diminished self-affection is a phenomenological term for an alienating, experiential state in which the patient does not feel entirely vital or present in this world.12 A meta-analysis by Hur et al. (2014)13 found that schizophrenia patients showed significant deficits in basic self-disturbances compared to healthy controls. These deficits were in the areas of– minimal self, body ownership and sense of agency suggesting an exaggerated sense of consciousness, or hyper reflexivity. Very recently, Monti et al. (2021),14 in their review, suggested that ‘interoception’ is vital to deficits in self-concept and might be underlying various symptoms across psychotic disorders apart from self-disorders, such as positive, negative and other cognitive symptoms. The task used in our study- the self-monitoring task, typically taps this aspect and therefore deem our results significant. The significant correlation between self-monitoring and PANSS scores we found in our study imply that self-monitoring (and therefore interoception) have remarkable impact on positive symptoms, in general.We conclude that schizophrenia patients show significant deficits in self-monitoring, which might be responsible not only for self-disorders, but also delusions and hallucinations.

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home