Official Journals By StatPerson Publication

|

Table of Content - Volume 6 Issue 2 - May 2018

Study of an impact of depression on the clinical course of asthma

Samyuktha G1, Ajaykumar Dhage2*

1Consultant Psychiatrist, Ameya healthcare HSR layout Bangalore, Karnataka, INDIA. 2Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, M. R. Medical College, Gulbarga, Karnataka, INDIA. Email: veda26@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Depressive symptoms are more common in asthma patients than the general population. Psychiatric forces such as co-morbid panic disorder, and depression may affect the clinical expression of asthma in several ways. Aim: To study an impact of depression on the clinical course of asthma. Material and Methods: In this prospective comparative study, seventy asthmatic patients between the age group 18-65 years were studied. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) was used to screen the subjects for depression. Asthma control was assessed using Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) which includes Forced Expiratory Volume (FEV1). These scales were administered at baseline, 3rd and 6th months post-treatment. Results: Of 40 asthmatics with depression, one patient had complete remission, while eight patients had PHQ9 scores 1-3 (minimal depression) at 6 months follow up. Depression had no significant correlation with asthma control at baseline. At 3rd month follow up, along with decrease in depressive scores (PHQ9), there was a significant decrease in ACQ scores, implying improvement in asthma control. There was no significant decrease in FEV1. At 6-months follow up, with reduction in depression scores, there was significant reduction (improvement) in both objective and composite measures of asthma control. Conclusion: Overall, there appears to be strong evidence of negative impact of depression on lung function among asthmatics. Depression had an impact on objective scores of asthma (FEV1), but did not have a significant impact on a composite measure (ACQ) of asthma control. Depressive scores at baseline could predict asthma control (composite scores) at 3rd month, but could not predict FEV1 scores. Key Words: Asthma, Depression, Patient Health Questionnaire, Forced Expiratory Volume, Asthma Control Questionnaire.

INTRODUCTION Asthma patients tend to have higher levels of stress and negative emotions such as panic, fear, irritability, depression and bipolar disorders. Greater anxiety is associated with increased perception of asthma-specific panic-fear and hyperventilation symptoms during an asthma attack, irrespective of depression status.1 Depressive symptoms are more common in asthma patients than the general population.2,3 Psychiatric forces such as co-morbid panic disorder, and depression may affect the clinical expression of asthma in several ways - altered awareness of airway resistance, suggestibility to airway constriction.4The present study was conducted to study an impact of depression on the clinical course of asthma.

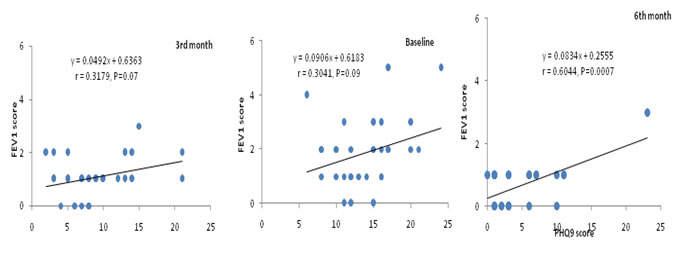

MATERIAL AND METHODS In this prospective comparative study, a total of 70 patients between 18-64 years with respiratory symptoms suggestive of airway disease registered at Department of Respiratory Medicine, in a tertiary care health center in Puducherry, India were assessed using spirometry. Patients aged 18-64 years, registering at the Department of Respiratory Medicine for the first time, with a diagnosis of asthma subsequently confirmed through spirometry and attending follow-up, registered not earlier than 3 months prior to date of current visit, already diagnosed as asthma usingspirometric criteria were included. A written informed consent was obtained from each patient. Patients with other co-morbid general medical conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, COPD, etc.), who have received psychiatric treatment elsewhere and are on treatment currently, who cannot perform spirometry, smokers and severely ill patients unable to co-operate for psychiatric evaluation were excluded from the study. Methodology: All patients were assessed using spirometry. A comprehensive systemic examination and laboratory investigations (hematology, biochemistry) were done to exclude co-morbid general medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid dysfunction, etc. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) used only to screen depression.Baseline ratings of PHQ were obtained from all asthmatic subjects. Group 1: Asthmatic subjects who received a significant score on PHQ-9 (asthmatics with depression) were classified as Group 1. Group 2: Asthmatic subjects who did not receive a significant score on PHQ-9 (asthmatics without depression) were classified as Group 2. Diagnosis made using PHQ-9 was verified by a consultant psychiatrist, using WHO ICD-10 Diagnostic Criteria for Research, through a formal psychiatric interview. Spirometric measurements that were obtained from newly registered cases for the purpose of confirming the diagnosis of asthma were treated as baseline values. Spirometric values of follow-up cases of asthma were recorded at the time of enrolment into the study, and were treated as baseline values for the purpose of this study, irrespective of prior spirometric values. Description of tools Spirometric Criterion -Forced Expiratory volume in one minute (FEV1): This method was used to measure airway limitation and reversibility to establish diagnosis of asthma. FEV1 values were monitored and it was a part of ACQ measured by clinician (objective finding). ACQ (Asthma Control Questionnaire): The ACQ has been validated to measure the adequacy of asthma management. Responses are given on a 7-point scale and the overall score is the mean of responses. The scale consists of 5 symptoms (shortness of breath, wheezing, waking dyspnea, nocturnal dyspnea, activity limitations) bronchodilator use and measurement of FEV1completed by the clinician. The ACQ has strong evaluative and discriminative properties and can be used with confidence to measure asthma control.5 Statistical Analysis: Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v 13.0), EPIINFO v. 6.0d and Microsoft Excel software. RESULTS The mean ages were 35.5 (39.4) and 42.5 (40.8) years for male and female patients respectively in asthmatic patients with depression (Group 1). In asthmatic patients without depression (Group 2) the mean ages were 30 (means: 34.2 for male and 31.4 for female) years for both genders. In both the Groups a large proportion of the participants were married (Groups 1 and 2: 78.1 and 70.0%) when compared to single (12.5 and 26.7%) or windowed 9.4 and 3.3%). The majority of the participants belong to lower upper lower income in both the Groups 1 (50%) and 2 (60%) followed by middle lower middle with corresponding figures of 31.3 and 26.7% respectively. Of the 70 asthmatic patients, 40 had depressive disorders giving an overall prevalence of 57.1%. Mild depression was seen in 15.7%, whereas moderate depression seen in 24.3%, and 2.9% had severe degree of depression. The prevalence of depression was higher among females (65.9%) than in males (42.3%). Among married persons the prevalence was 59.6% and that among unmarried, it was 38.5%. Of the five widowed persons four had depression. The prevalence was 51.9 and 60.5% among participants from upper or middle and lower socio-economic classes, 61.3 and 53.8% from urban and rural respectively. The somatic form and anxiety disorders were observed among 3 and 6 of the 70 patients giving an overall prevalence of 4.3 and 8.7% for the two forms disorders respectively. Asthmatic patients with depression: The association of PHQ9 score with FEV1 at baseline and 3 and 6 months post-treatments are depicted in Figure 1. While at baseline (r=0.3041, P=0.09) and 3 months post-treatment (r=0.3179, P=0.07) no significant correlations were observed between PHQ9 score and FEV1 score, at 6-months post-treatment significant positive correlation (r=0.6044, P=0.0007) was observed between the two variables.

Figure 1: Association of PHQ9 score with FEV1 score at base line, 3 and 6-months post-treatment among Group 1(Asthmatics with depression)

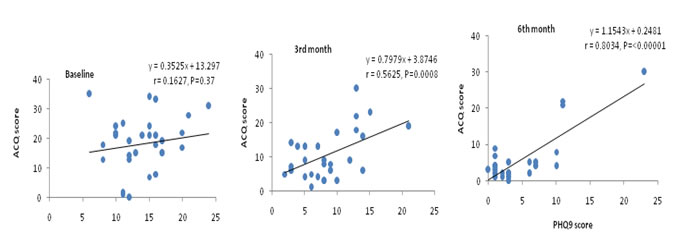

Figure 2 shows the association between PHQ9 with ACQ scores. Significant positive associations were observed between PHQ9 and ACQ scores both at 3 months (r=0.5625, P=0.0008) and 6 months (r=0.8034, P<0.0001) post-treatment. However, at baseline no significant association was observed (r=0.1627, P=0.37).

Figure 2: Association of PHQ9 score with ACQ score at base line, 3 and 6-months post-treatment among Group 1

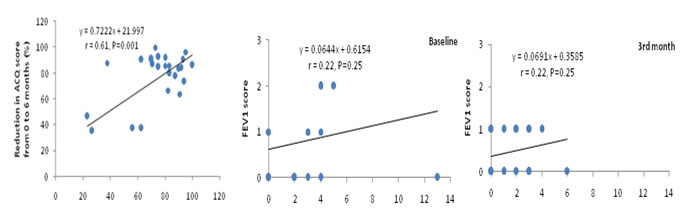

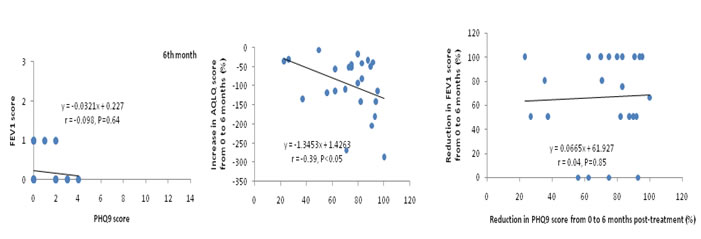

Asthmatic patients without depression: The FEV1 score had no significant association with PHQ9 score at baseline, 3 and 6-months post-treatment (Fig. 3). Whereas PHQ9 score had significant positive and negative associations with the scores of ACQ (r=0.5779, P=0.0008) at 3 months post-treatment (Figs. 13 & 14). However, these variables did not significantly associate at baseline or 6-months post-treatment.

Figure 3: Extent of improvements in ACQ, AQLQ and FEV1 scores at 6 months post-treatment in relation to that of PHQ9 score Figure 4: Association of PHQ9 score with FEV1 score at base line, 3 and 6-months post-treatment among asthmatics without depression

The mean scores of PHQ9 and ACQ significantly declined at 3 and 6 months post-treatment when compared to their corresponding scores at baseline (one way ANOVA followed by post-hoc test based on LSD, P<0.05 for all comparisons).

DISCUSSION Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease whose main characteristic is a huge variability in its clinical expression. Even when disease control is achieved, all asthma patients have to deal with the risk of future exacerbations and the decrease in pulmonary function. These features might lead to an ongoing stress situation. FEV1 score is considered to be an objective finding of asthma control. Lower scores indicate well controlled asthma and higher scores indicate poorly controlled asthma.It was observed that there were no significant correlations between PHQ9 score and FEV1 score at baseline and 3 months follow up, while at 6-months follow up significant positive correlation was observed between the two variables in asthmatics with depression. The FEV1 scores for asthmatics with depression were always higher than asthmatics without depression. Comparison of the FEV1 scores between the groups indicated that asthmatics with depression had significantly higher scores at baseline (1.8 vs 0.9) and at 3 months post-treatment (0.9 vs 0.5) but not at 6 months post-treatment (0.5 vs 0.2). The findings in the study indicated an association between depression and FEV1 scores. Kromydaas et al6 also observed a statistically significant reduction in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC values in asthmatic patients with symptoms of depression. The mean value of FEV1 was 81.84 in patients without symptoms and 63.73 in patients with symptoms of depression. Similar findings were reported by Di Marco et al.7 However, Rimington et al8 did not find any correlation between depression and lung function among asthmatics. Overall there appears to be strong evidence of impact of depression on lung function among asthmatics. Impact of depression (PHQ9 score) on Asthma control (ACQ): The asthma control questionnaire consists of both FEV1 and few questions answered by the patients. Lower scores of ACQ imply well controlled asthma and higher scores imply poorly controlled asthma. Depressive scores had a significant association with asthma control. Higher score of depression was associated with poor asthma control. This association was found at 3rd and 6th months follow up. However, at baseline no significant association was observed. Composite measures of asthma control did not differ between asthmatics with depression and asthmatics without depression at baseline and 6th month follow up. Unlike this study, two studies reported of asthmatic patients with depression having poor asthma control.9,10 Significant correlations were found between changes in ACQ score and HAM-D-17 by Brown et al.11It is interesting to note that asthmatic patients with depression had significantly higher total ACQ scores at 3 months post-treatment compared to patients without depression. Depression had an impact on objective scores of asthma (FEV1), but did not have significant impact on composite measure (ACQ) of asthma control. It is pertinent to note that the findings in this study with regard to impact of depression on asthma control (ACQ) are contradictory to other studies. This issue merits further research.

CONCLUSION The study suggests that patients with asthma have a high prevalence of depression. Overall, there appears to be strong evidence of negative impact of depression on lung function among asthmatics. Depression had an impact on objective scores of asthma (FEV1), but did not have a significant impact on a composite measure (ACQ) of asthma control. Depressive scores at baseline could predict asthma control (composite scores) at 3rd month, but could not predict FEV1 scores. There was significant difference between groups related to the objective findings of asthma control (FEV1), but no difference could be noted for composite measure of asthma control (ACQ). These findings were contradictory to the finding of other researchers, implying need for further clarification.

REFERENCES

|

|

Home

Home