Official Journals By StatPerson Publication

|

Table of Content - Volume 12 Issue 3 -December 2019

Ultrasound guided preoperative assessment of gastric antral cross-sectional area with respect to fasting hours to avoid the pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents

Praveen Dhakite1, Manasi Panat2*

1Junior Resident III, 2Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesia, JMF’s A.C.P.M. Medical College, Dhule, Maharashtra, INDIA. Email: mapanat7498@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Pulmonary aspiration of the gastric contents is a serious peri-operative complication. Aim: The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of portable ultrasonography in the preoperative evaluation of gastric antrum cross sectional area with respect to number of fasting hours. Methods: This single-center, prospective, cross-sectional study included 120 patients who underwent surgery. Measurements of the gastric antral cross-sectional areas and quantitative and qualitative measurements of the stomach were taken by ultrasonography guidance in all patients. Result: With the patient in a supine position, the mean gastric antrum cross-sectional area was found to be 3.4±2.43 cm2 (range, 0.79–17.3 cm2). As the number of hours of fasting increased, the gastric antral cross-sectional area statistically significantly decreased (P<0.05). Increased age and BMI values were determined to increase the gastric antrum cross-sectional area in a linear correlation; r=0.209, P<0.05 and r=0.252, P=0.05, respectively. It was determined that 20.8% of the patients exceeded the high-risk stomach antral cutoff cross-sectional area that was defined as 340 mm2 in patients fasting for at least 8 hours. Conclusion: It was determined that bedside ultrasonography is a useful, non-invasive tool in the determination of gastric content and volume. A significant proportion of surgical patients may not present with an empty stomach despite the recommended fasting protocols. Key Words: Fasting, Pyloric Antrum, Pulmonary Aspiration of Gastric Contents, Ultrasonography.

Although perioperative aspiration of the stomach contents is seen rarely in anesthesia practice, it is a complication that can lead to severe perioperative morbidity and mortality1,2. The risk of morbidity and mortality has been reported as 8%–10% in large case series studies that included long-term mechanical ventilation as a result of aspiration pneumonia3,4. However, different clinical conditions emerge depending on the type and amount of aspirated material, the frequency of aspiration, and the response of the patient. Factors increasing morbidity include

Identification of patients at risk is a cornerstone of safe anesthesia practice regarding preoperative fasting and therapeutic drug aspiration. General anesthesia or sedation block the physiological mechanisms preventing aspiration (lower esophagus sphincter and upper airway reflexes)5. Therefore, the liquid and solid food intake of a patient before general anesthesia is important for patient safety. In the revised preoperative fasting guidelines, at least 2 hours without clear liquids is recommended, 6 hours of fasting for liquids containing solid particles and toasted sandwich type solid foods, and 8 hours of fasting for high calorie and fatty foods6. For patients at risk of aspiration, rapid sequence induction, tracheal intubation without mask ventilation, or face mask ventilation with cricoid pressure are recommended 7.The primary aim of this prospective study was to identify patients at risk of perioperative aspiration of stomach contents, by calculating the gastric antrum cross-sectional area with preoperative stomach antrum Ultrasonography of patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS Source of data: Study included 120 patients who underwent surgery after considering inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study Design: Single-center, prospective, cross-sectional study Study Period: During the period of one year from September 2018 to September 2019. Study Place: Department of anesthesia and critical care at JMF’s ACPM Medical college, Dhule Sample size: 120 After approval of ethical committee, written and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

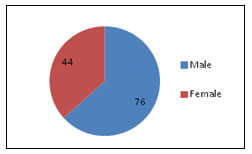

Pre Procedural Assessment: In the preoperative section of the operating theater, all patients were questioned in detail about their fasting status, demographic data were recorded, and a medical examination was made. Before anesthesia induction, the fore mentioned described standardized screening protocol was applied to the patients for gastric examination and USG by an experienced USG operator (with at least 5 years USG experience and >50 gastric USG examinations). The doctor applying the USG had no influence on the anesthesia method or any other procedures applied to the patient. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the gastric antrum was made by the USG operator. RESULT The study included a total of 125 patients. Five patients were excluded: where detailed images could not be taken because of gas in the stomach. Therefore, the study evaluation included 120 patients of which 76 were male and 44 were female; the mean age was 40.4±16.54 years (range, 18–82 years). Figure 1: Distribution of Patients The study evaluation included 120 patients of which 76 were male and 44 were female. The mean age group of the patients was in the range of 40.4±16.54 years. The demographic data of the patients are recorded. A period of more than 8 hours of fasting was determined in 91 patients (75.8%) and less than 8 hours of fasting in 29 patients (24.2%). The mean cross-sectional area of the stomach antrum was found to be 3.34±2.43 cm2 (range, 0.79–17.3 cm2.

Figure 2: No of patients with antral cross-sectional area w.r.t hours of fasting

DISCUSSION The results of this study showed that the ultrasonography can be effectively used for preoperative gastric antrum measurements in patients for the examination of stomach contents. It was observed that as the period of fasting increased, the stomach antrum area decreased, in the different periods of fasting. In patients with at least 8 hours of fasting, a statistically significant change was determined in the stomach antrum area, independent of factors such as age and BMI. Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents is one of the most feared complications of anesthesia, which was reported to be one of the important causes of mortality related to general anesthesia 1,2,3,4. One of the risk factors for the occurrence of pulmonary aspiration and mainly for the onset of its clinical consequences is the volume of the aspirated gastric content. In 1946, Mendelson first identified pneumonia associated with the aspiration of gastric contents during general anesthesia in obstetric patients, and this complication has since been emphasized as a serious problem in anesthesia practice8 . Severe complications, such as pneumonia, pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and hypoxic brain injury, are associated with aspiration9 .Ultrasonography is being used in anesthesiology for peripheral and central nerve blocks, venous and arterial punctures, orotracheal intubation interventions and cardiac interventions. Bedside determination of gastric fullness with Ultrasonography has been used successfully in intensive and emergency care units for the evaluation of the risk of pulmonary aspiration10. Koenig et al. determined the stomach contents of intensive care patients who were to be intubated in the supine position using Ultrasonography. He then aspirated the stomach contents and applied the procedures19. The volume of gastric content is defined with different mathematical models after the calculation of the gastric antrum cross-sectional area with Ultrasonography imaging10,11,12,13.The cut-off values of gastric volume which would lead to aspiration of stomach contents have been a topic of debate. Previous studies have shown basal values of gastric content volume varying between 100 mL and 130 mL in individuals with an average fasting period, which has been shown to be equivalent to 0.6 mL/kg15,16,20,21. While the stomach content of 25–50 mL volume (0.4–0.8 mL/kg) has been accepted as the cutoff value in animal studies adapted to humans22. In some studies, gastric antrum area measurements of 320 mm has been taken as a threshold value for risk evaluation2,18,19 23,24. According to the results of the current study, in 20.8% of the patients with a fasting period of at least 8 hours, the antral cross-sectional area was higher than 340 mm. In the current study, no statistically significant difference was determined in the antral cross-section measurements of those undergoing elective or emergency surgery. Due to the low number of patients, and because the majority of those in the emergency patient group were appendectomy cases who had delayed time to admittance for surgery for diagnosis from fasting periods, the period of fasting exceeded the mean 8 hours. This study had few limitations specific patient groups such as children, Pregnant patients, the elderly, and those with certain co-morbidities were not included in this study. A single practitioner could do ultrasonography examinations and the results could not be confirmed by another radiologist. A clear mathematical formula related to the stomach content volume could not be derived as the study was conducted with the patients in a supine position. Hence, high risk stomach classification could not be applied according to the estimated gastric content volume.

CONCLUSION It was determined that the use of bedside USG was simple and effective in the examination of stomach content volume and the evaluation of the related risk of aspiration. It should be taken into consideration that patients have a risk of gastric filling despite recommended fasting protocols, increased age, and BMI.

REFERENCES

|

|

Home

Home