|

Table of Content - Volume 13 Issue 2 -February 2020

Comparative evaluation of transnasal dexmedetomidine and transnasal midazolam for premedication in children undergoing anesthesia: A double‑blind randomized clinical trial

Manjunath C Patil1*, Pavan Dhulkhed2, Narendra Malineni3

1Professor, 2Assistant Professor, Department of Anaesthesiology, J.N.Medical College, Belgaum 590010. 3Assistant Professor, Dept of Anaesthesiology, Pinnamaneni Siddartha Medical College, Gannavaram. Vijaywada. Andra Pradesh. Email: mcpatil52@gmail.com,pavandhulkhed1984@gmail.com,drnaren28@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Children posted for surgeries experience anxiety in perioperative period. Sedative premedications used, reduce anxiety and help in smooth induction of anesthesia. Midazolam is commonly used to overcome anxiety has adverse effects like behavioral changes, hiccups, etc. Dexmedetomidine, a highly selective alpha 2 agonist, also has sedative properties. Aims and objectives: To compare the efficacy of transnasal dexmedetomidine and transnasal midazolam as premedicants in pediatric age group for parental separation anxiety and anesthesia mask acceptance. Methods: This study included 60 American Society of Anesthesiolosits I–II children between 1–10 of years posted for lower abdominal and lower limb surgeries under caudal anesthesia. After Ethical committee’s clearance and informed consent, the child was allocated to either groups by a computer generated randomization table to receive 0.2 mg/kg midazolam (Group M) and 1 mg/kg dexmedetomidine (Group D) transnasally. Parental Separation Anxiety Scale (PSAS) and Mask Acceptance Scale (MAS) were assessed. Results: Demographic data was comparable in both groups (P > 0.05). Mean PSAS was 1.2 ± 0.40 in dexmedetomidine group and 1.6 ± 0.56 in midazolam group (P = 0.003). Mean mask acceptance score (MAS) at the time of induction was 1.7 ± 0.59 in dexmedetomidine group and 2.1 ± 0.58 in midazolam group (P = 0.02). Conclusions: Transnasal dexmedetomidine 1 mg/kg is an effective alternative for premedication in children undergoing anesthesia and with better parent separation and mask acceptance compared to transnasal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg. Keywords: Anxiety; Dexmedetomidine; Intranasal; Midazolam; Premedication.

INTRODUCTION

How to cite this article: Abinaya Rajasekaran, Kamalakannan Manian. Comparative study of effect of clonidine 0.5 mcg/kg and 1 mcg/kg as an adjuvant to 0.5 % bupivacaine in Ultrasound guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. MedPulse International Journal of Pathology. February 2020; 13(2): 127-132. https://www.medpulse.in/Pathology/

MATERIAL AND METHODS After obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee and informed consent, sixty ASA I or II children aged 1–10 years, posted for lower abdominal and lower limb surgeries under caudal epidural anesthesia with sedation between January 2017 and December 2017, were enrolled and randomly divided into two groups by a randomization table which was generated by a software, into Group M receiving 0.2 mg/kg transnasal midazolam (up to a maximum 5 mg) and Group D receiving 1 g/kg dexmedetomidine transnasally using 1 ml tuberculin syringe with children in recumbent position 45–60 min before shifting them to operating room (OR). Exclusion criteria were children with known allergy to dexmedetomidine or midazolam, cardiac arrhythmia, heart disease, rhinitis, and delayed milestones. Baseline heart rate (HR) and oxygen saturation (SpO2) were noted and monitored for every 5 min after administration until patients were transferred to OR. To avoid bias, all observers and attending anesthesiologists were blinded for the study drug given. Parental separation anxiety and Anaesthesia mask acceptance were evaluated by the anesthesiologist who induces the baby. Parental separation anxiety was assessed using the Parental Separation Anxiety Scale (PSAS), which is a 4‑point scale.

The child’s ability to accept the anesthesia mask during induction in the OR was measured using Mask Acceptance Scale (MAS).

Further, the monitors were attached and patients were induced using sevoflurane and IV. cannula secured. After induction, all patients were given caudal epidural anesthesia using 1 ml/kg body weight of 0.25% bupivacaine and maintained with O2± N2O using a face mask. Adverse events, if any, were noted till the end of the procedure. Sample size was calculated by considering the incidence of satisfactory mask induction of dexmedetomidine sedation as 53% and that of midazolam as 18%,7 with Type I error rate =0.05 and Type II error rate = 0.02 with a power of 80%. Wilcoxon rank‑sum test was used to determine difference between the two groups for means of the PSAS and mask acceptance scale. Quantitative data such as HR and SpO2 were analyzed using Student’s t‑test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

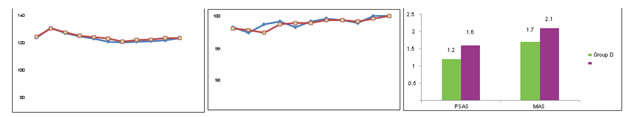

RESULTS In our study, demographic characteristics were comparable in both groups and there was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between the groups [Table 1]. Intranasal The mean PSAS was 1.2 ± 0.40 in dexmedetomidine group and 1.6 ± 0.56 in midazolam group which is statistically significant with P = 0.003. The mean mask acceptance score (MAS) at induction of anaesthesia was 1.7 ± 0.59 in group D and 2.1 ± 0.58 in group M which is statistically significant (P = 0.020). Only 2 (6.6%) children in dexmedetomidine group had MAS > 2 when compared to 6 (20%) children in midazolam group [Table 2]. Table 1: Demographic data

Table 2: Parental Separation Anxiety Scale and MAS

Figure 1: Preoperative mean heart rate; Figure 2: Preoperative mean oxygen saturation; Figure 3: Parental Separation Anxiety Scale and MAS DISCUSSION Children undergoing surgery experience excessive anxiety and stress during the perioperative period which can lead to adverse outcome postoperatively. Kain demonstrated that 54% of their patients had negative behavioral patterns at 2 weeks and 20% continued to have these patterns up to 6 months.8 The beneficial effects of midazolam as a premedicant include sedation, anxiolysis, and amnesia. However, midazolam is associated with respiratory depression and lacks analgesic property. A high incidence of adverse postoperative psychological changes and temper tantrums have also been observed. Dexmedetomidine is a newer ‑2 agonist with a more selective action and a shorter half‑life compared to clonidine. There is increasing evidence that dexmedetomidine is an effective and safe sedative in children and has analgesic property.9 It also reduces anesthetic requirement and does not cause respiratory depression. Transnasal application is a relatively noninvasive, convenient, and easy route of administration, not requiring patient cooperation as would be the case for swallowing the medication in oral route or retaining it sublingually. Transnasal administration has faster onset of action and also reduces first‑pass metabolism. Transnasal midazolam has been used in various doses (0.01–0.5 mg/kg) as a premedicant. Davis et al. in a dose‑finding study of transnasal midazolam showed that the percentage of satisfactory separation (91% vs. 90%) and induction scores (60% vs. 80%) were comparable in case of 0.2 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg dose, respectively.10 Hence, we decided to administer 0.2 mg/kg midazolam as premedicant by transnasal route. Transnasal dexmedetomidine has been used in doses ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 g/kg. In a comparative study by Yuen et al., it was shown that 75% of the children in dexmedetomidine 1 g/kg group had satisfactory sedation when compared to 59.4% in 0.5 g/kg group.11 Ghali et al. showed that dexmedetomidine is effective and safe intranasally in 1 g/kg dose. Hence, we decided to use 1 g/kg dexmedetomidine intranasally.12 Dexmedetomidine is known to decrease sympathetic outflow and circulating catecholamine levels and therefore would cause a decrease in HR. In a pharmacokinetic study of IV dexmedetomidine in children, it was shown that 0.66–1 g/kg IV dexmedetomidine, given over 10 min, produced a significant reduction of HR >15% compared with baseline.13 In our study, HR was decreased by 2% from baseline at 10 min and 9.1% from baseline at 30 min after transnasal dexmedetomidine premedication. Similarly, HR was decreased by 8.8% from baseline at 30 min after transnasal midazolam premedication [Figure 1]. In a comparative study of transnasal dexmedetomidine with oral midazolam by Yuen et al., HR was decreased by 11.1% and 16.4% from baseline in patients who received 0.5 and 1 g/kg transnasal dexmedetomidine, respectively, during the 1st h after the administration of the drug. However, these effects were clinically insignificant, and no intervention was required.11 In another similar comparative study by Akin et al., reduction in HR of 6.7% from baseline in the transnasal dexmedetomidine and 7% from baseline in the transnasal midazolam group was noted.7 There was no evidence of fall in oxygen saturation, reduction in respiratory rate or apnea in our study, which was similar to the study done by Davis et al, on 88 children, which indicates that the doses used for both transnasally administered midazolam and dexmedetomidine are safe and comparable to the findings of other studies.10,11 In our study, the baseline mean SpO2 was 99.1% in midazolam group which was comparable to 99.2% in dexmedetomidine and the difference was not statistically significant. None of the patients in both groups had SpO2 <95% at any point of time during preprocedural monitoring [Figure 2]. Similarly, in a comparative study between transnasal midazolam and dexmedetomidine, SpO2% was comparable and none of the patients had SpO2 <95% at any point of time.7 We also evaluated parental separation anxiety in children. Parental separation anxiety has been assessed by different scales by different authors. Yuen et al. have also evaluated parental separation anxiety.11 Ghali et al. used a 3‑point scale12 and Akin et al. used a 4‑point scale at 30 min7 for parental separation anxiety. In our study, we decided to assess PSAS using a 4‑point scale. Our results show that a dose of 1 g/kg transnasal dexmedetomidine premedication is capable of producing a satisfactory PSAS when compared to 0.2 mg/kg transnasal midazolam (P = 0.003) [Figure 3]. This was similar to a study done by Sheta et al.14 who compared 72 children and found that children in dexmedetomidine group were significantly more sedated than midazolam group when they were separated from their parents (P = 0.002). Recently, Akin et al.7 conducted a study comparing transnasal midazolam and dexmedetomidine on children, aged between 2 and 9 years. Doses similar to that utilized in our study were utilized and administered approximately 45–60 min before the induction of anesthesia. They reported that there was no evidence of a difference between the groups in anxiety score (P = 0.56) upon separation from parents. Many authors have evaluated behavior of the child while entering and/or quality of mask acceptance.7,14 We assessed acceptance of mask and behavior under sedation. In a study conducted to compare midazolam and dexmedetomidine for premedication in children undergoing complete dental rehabilitation,14 Sheta et al. observed that children in dexmedetomidine group were significantly more sedated and had satisfactory compliance with mask application (80.6% vs. 58.3% [P = 0.035]). Faritus et al. studied the effect of dexmedetomidine and midazolam on sixty children13 and showed a better effect on the mask acceptance behavior (mean mask acceptance score of 2.58 ± 0.6 and 1.6 ± 0.67 for midazolam and dexmedetomidine, respectively; P < 0.05). Our results show that the mean mask acceptance score (MAS) at the time of induction in dexmedetomidine group was 1.7 ± 0.59 when compared to 2.1 ± 0.58 in midazolam group, which is statistically significant (P = 0.020). Hence, we found that transnasal dexmedetomidine provides better mask acceptance score than transnasal midazolam in children. Our study did not specifically address the issues of the patient acceptance of the drug. In a study done by Sundaram comparing transnasal midazolam and transnasal dexmedetomidine, seven children receiving midazolam were noted to become euphoric or restless after premedication, but none after dexmedetomidine.15

CONCLUSION In our study, we conclude that transnasal dexmedetomidine 1 g/kg is more effective and a safe for premedication in children undergoing lower abdominal surgeries under caudal epidural anesthesia, has good parent separation and mask acceptance at anaesthesia induction in comparison with transnasal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg without causing much side effects or postoperative complications.

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

Home

Home