|

Table of Content - Volume 17 Issue 1 - January 2021

A case series in anaesthetic management in a patient with Brugada syndrome

R Arun Kumar1*, Dalena Merin Mathew2, Reehana Jabarulla3, P Mahalakshmi4

1Associate Professor, 2Assistant Professor, 3,4Junior Resident, Department of Anaesthesiology, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Coimbatore Email: shivaaniarun76@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Brugada syndrome also termed as Pokkuri death syndrome or Sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome, is a condition with characteristics ECG changes in ST elevation noted in the anterior leads V1-V3 with apparent Right bundle branch block in structurally normal heart, which may present with tachyarrhythmia, syncope, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation or sudden death at sleep. The etiology of cardiac disease Brugada syndrome is caused by an inherited ion channelopathy associated with development of irregular cardiac rhythmic activity. Key words: Brugada syndrome, Anaesthetic concerns, Perioperative care, Ventricular fibrillation, Sudden cardiac Death

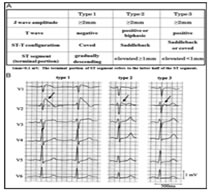

INTRODUCTION Brugada syndrome was described by Pedro and Joseph Brugada in 1992 as a cause of sudden cardiac death. It is a hereditary arrhythmias characterized by a specific ECG pattern and an increased risk of sudden cardiac death with an apparent absence of structural abnormalities or Ischemic heart disease.1 Here with we discuss the management of three different cases of Brugada syndrome planned for surgeries. CASE SERIES I A 45 years aged male, asymptomatic patient presented with fracture right patella following a fall in the road, posted for right tension band wiring (TBW) for patellar fracture. Patient had no significant medical comorbidities or past significant surgical history. No history of smoking, alcohol intake and there wasn’t any history of sudden cardiac death in the family. On preoperative evaluation for TBW, patient’s ECG revealed type I ECG pattern – a coved ST segment elevation > 2mm in V3 and V4 followed by a negative or flat T wave which is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. All other investigations were within normal limits. Epidural anesthesia was planned for TBW. Defibrillation pads were used to monitor cardiac rhythm along with standard ASA monitors. Under strict aseptic precautions, epidural catheter was placed at L3-L4 level on first attempt and 2% lignocaine with adrenaline 3cc test dose was given. Patient was placed supine and a top up epidural in graded doses was given, with a maximum of 14 ml lignocaine with adrenaline. Level of blockade achieved was L1. TBW was done in one hour 20 minutes. Epidural catheter was removed at the end of the procedure. Post operative pain management was supplemented with intravenous paracetamol. Patient was haemodynamically stable throughout the procedure and was monitored in High dependency unit (HDU) for 24 hours. CASE SERIES II 37 year aged male presented with swelling in the front of the neck extending to the left lateral side who was provisionally diagnosed as Neck abscess secondary to bacterial infection was planned for incision, drainage and exploration of abscess. CT scan neck revealed abscess collection in the anterior and posterior triangle of the neck without extension into the retropharyngeal space. No significant past medical history of any systemic illness. Blood investigations including biochemical, renal and coagulation parameters were within normal limits. ECG revealed coved type ST segment in V1 and V2. Cardiologist opinion was obtained and was diagnosed as Brugada syndrome clinically. Informed and written consent was obtained explaining the conduct of general anaesthesia and the consequences of Brugada sequlae were briefly described prior to conduct of anaesthesia.

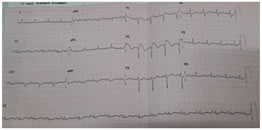

Figure 1: Electrocardiographic Recordings of patient Anaesthesia was conducted after supplementing anti aspiration prophylaxis with Ranitidine. General anaesthesia supplemented using Intravenous Midazolam 1.5mg, Fentanyl 100µg, Propofol 120mg and 20mg in two aliquots, supraglottic airway device (proseal LMA) with spontaneous ventilation achieving MAC 1.3 (O2 in N2O with sevoflurane). Injection Paracetamol 1 gm was supplemented as analgesia and Injection Dexamethasone 4 mg for Postoperative nausea and vomiting and as antiaspiration coverage. Duration of the procedure was 25 minutes, intraoperative period was uneventful and towards the end of the surgery patient was extubated. CASE SERIES III 47 year aged male diagnosed as Brugada syndrome with no clinical cardiac symptomatology presented with abdominal pain, nausea and fever for about 2 days. Clinical suspicion was duodenal perforation and planned for laparotomy for perforation patch closure. Biochemical and renal parameters were within normal limits except ECG changes. Risk consent obtained explaining the consequences of general anaesthesia, need for ICD and invasive arterial lines. Anaesthesia was induced with intravenous Midazolam 1.5mg, Fentanyl 100µg, Propofol 120mg after securing right radial arterial line for monitoring blood pressure; intubated with 4MAC blade using 8.5cETT and Atracurium 30mg and maintained with O2 in air, sevoflurane achieving a MAC of 1 to 1.2. Intraoperative period was uneventful; required one incremental dose of Atracurium and the duration of surgery was about 100 minutes. Paracetamol 1gm was supplemented as an analgesic and at the end of the surgery, Lidocaine 40mg IV supplemented to alleviate the stress response. Patient had spontaneous return of respiratory efforts and good muscle tone favouring extubation without use of reversal of neuromuscular blocking agent. Post extubation patient was stable haemodynamically and monitored in HDU.

DISCUSSION Brugada syndrome also termed as Pokkuri death syndrome (PDS), sudden unexpected death syndrome (SUDS) or Sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), is a condition with characteristics ECG changes (ST elevation in the anterior leads V1 - V3 with apparent Right bundle branch block) in structurally normal heart2, which may present with tachyarrhythmia, syncope, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation or sudden death at sleep1. Brugada syndrome is most prevelant in young adult males of south East Asian descent, but it has been documented in both genders, all age groups and a variety of ethnic population accounting for prevalence ranging from 1 in 5000, incidence about 0.12-0.8% recorded from electrocardiogram3 and 0.05 % - 0.6% of cases of SCD4. The etiology of cardiac disease Brugada syndrome is caused by an inherited ion channelopathy associated with development of irregular cardiac rhythmic activity. It follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with variable presentation and expression. In approximately 25% of families, Brugada syndrome is the result of a defect in SCN5A gene on chromosome 3, which encodes the alpha submit of the sodium channel and in another 25% of cases, the inheritance pattern is not clear but is felt to be the allelic disorder of the sodium channel gene. The remaining 50% of cases have no family history and are postulated to be the result of sporadic mutation5.

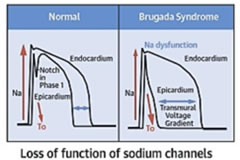

Figure 2: Pathophysiology depiction of Brugada syndrome5 The pathophysiology of Brugada syndrome appear that the sodium channels of the right ventricular epicardium are affected and not the endocardium. This alteration of action potential in the epicardium causes differential repolarization and refractoriness across the myocardium leading to a vulnerable period during which a premature impulse or extra systole can trigger a recent dysrrythmias4. Certain physiological and external factors can unmask or exacerbate the channel dysfunction. These include febrile episodes, autonomic imbalances, electrolyte disturbances; drugs that affect the sodium channels particularly class Ia and Ic, antidysrhythmics, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, Benadryl and cocaine2. The predominant risk factors for the arrythmogenic potential in Brugada includes spontaneous type I ECG pattern, prolonged QRS, T wave alternans, early repolarization pattern in inferolateral leads, male sex, syncopal episodes, nocturnal agonal respiration, previous episodes of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation6. Figure 3: Various ECG Types of Brugada Autonomic changes and multiple pharmacological interactions commonly seen during anesthesia may exacerbate the underlying disease process and trigger Brugada ECG changes and malignant arrhythmias. Beta blockers, alpha agonists, vagotonic agents have been shown to exacerbate the ECG changes7, typical of brugada, as having pressure on carotid body, perioperative hypothermia, light anesthesia and post operative pain. Local anaesthetic especially bupivacaine given by any route cause a sudden rise in the serum concentration, can unmask brugada syndrome. Class IIb antiarrhythmic drug Lignocaine has no such effect and can be safely used7. Syncope is the commonest presenting symptom and idiopathic in majority of cases. Hence this order is of specific concern to anaesthesiologist as they routinely administer drugs that interact cardiac ion channels which theoretically could trigger the development of malignant hypothermia. There are few report of regional technique used as the primary anaesthetic technique8. Two of the three reported cases involving epidural anesthesia reported problems, where Bupivacaine was used in both the cases and there was no preoperative diagnosis of Brugada syndrome. The changes completely resolved on discontinuation of epidural bupivacaine infusion. An asymptomatic patient with an unrecognized preoperative brugada ECG underwent general anesthesia combined with a thoracic paravertebral block using 40ml 0.5% Ropivacaine9. The patient developed intra operative bradycardia, hypotension and unstable ventricular tachycardia requiring inotropic support shortly after surgery was commenced. An epidural bupivacaine infusion had been administered to a known young brugada patient with palpitations but reported without any anticipating incident10. One report of spinal anesthesia using 10mg of 0.5% bupivacaine for repair of patella fracture which was uneventful intraoperatively11. From the cases described, there is conflicting evidence regarding the anesthesia techniques12 and regional anesthesia is safer; but care should be taken to monitor the unmasking effect of arrhythmias under regional anaesthesia. Autonomic nervous system to neuraxial anaesthesia effects also plays a pivotal role apart from local anaesthetic systemic action in brugada individuals13. In our case, we decided on epidural anesthesia for first patient and the local anaesthetic used was lignocaine with adrenaline which was administered in graded doses to achieve a blockade at L1 level. Continuous monitoring of ECG, NIBP and SpO2 was done. Patient was haemodynamically stable throughout the procedure. Epidural catheter was removed at the end of the procedure. Post operative management was taken care with intravenous paracetamol and tramadol. Literature reveals complications with Bupivacaine14 and Prilocaine15 during neuraxial anaesthesia suggesting the unmasking effect of arrhythmias. We were deliberate to give general anaesthesia for our second case inview of abscess involving near the neck and preferably focusing on airway maintainence also considering the risk stratification of the coexisting syndrome. Knowing that the general anaesthesia can aggravate the autonomic nervous system and can produce various tachyarrhythmias, meticulous care taken at the time of conduct of anaesthesia keeping all backup ready. Flamee et al.16 in his randomized study with the action of Propofol on electrocardiographic pattern of any degree confirmed that there was no signals in detection of malignant arrhythmias triggered by Propofol and its use as induction agent of anaesthesia in Brugada individuals was considered safe. The mechanism postulated17 was that it could be due to the inhibition effect of the transient potassium current in the right ventricle outflow epicardial cells and repolarization related arrhythmic abnormalities. A single dose of propofol usually exhibits adjustment and rebalancing in the ionic channel currents18. In our last case, we used general anaesthesia with controlled ventilation in view of upper abdominal surgery for safe conduct of anaesthesia and surgery. Emergency cardiac drugs, ICD and all resuscitation drugs were kept ready prior to conduct of anaesthesia. There was no hypoxia, hypercarbia, hypothermia, acidosis or alkalosis intraoperatively. Crystalloids were used for intravascular volume replacement and detailed pharmacological interventions were planned. Smooth conduct of anaesthesia conducted with cardiologist backup for emergency intervention in view of known Brugada syndrome. Implantable cardiac defibrillator is the only established effective therapy in the management of Brugada syndrome and the use of pacemaker, ablation or cryosurgery is still controversial. Beta adrenergic agonists (isoproterenol), Quinidine, phosphodiesterase inhibitors (Cilastazol) and cardio selective blockers are definite pharmacological therapy; Amiodarone and beta blockers does not have any beneficial effect, class Ic and class Ia antiarrhythmic and procainamide are contraindicated19,20. As the condition is increasingly recognized, so more patients are likely to present for anesthesia for treatment of syndrome by implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) insertion or for nonrelated cardiac surgery. We as anaesthesiologist have to take care, when using alpha agonist and neostigmine and to avoid Class I antiarrthymic drugs. Lignocaine has proved to be safe, but still precaution to be taken about the dose used as rapid absorption into the systemic circulation may be cause for cardio vascular instability in brugada syndrome patients20.

CONCLUSION Brugada syndrome is an increasingly recognized syndrome and the importance of detecting Brugada is due to its high prevalence in the Asiatic young population. Patients undergoing anaesthesia should be monitored continuously during peri-operative period with extended care in the High dependency unit post operatively so that any cardiac arrhythmias can be timely detected and treated21.

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access: Authors who publish with MedPulse International Journal of Anesthesiology (Print ISSN:2579-0900) (Online ISSN: 2636-4654) agree to the following terms: Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post links to their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work.

|

Home

Home