Official Journals By StatPerson Publication

|

Table of Content Volume 11 Issue 2 - August 2019

A study of immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in nursing staff at a tertiary care hospital

Rashmi Chandragouda Meti1, Anand Nagalikar2*

1Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology, Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences, Narketpalli Telangana, INDIA. 2Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, ESIC Medical College Kalaburagi, Karnataka, INDIA. Email: anagalikar@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is highly infectious and causes serious health problems worldwide. Nursing staff are at high risk for HBV infection because of particular exposure of mucus membranes and breached skin to blood. Aim: To evaluate immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in nursing staff at a tertiary care hospital. Material and Methods: A total of 70 nursing staff were included in the study. Vaccination status was recorded. Blood samples were tested for hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) titre using a commercial kit. Protective antibody titre levels equal or more than 10 mIU/mL for HBsAb were considered to be protective. Results: Of the 70 nursing staff studied, 6 (8.6%) received only one dose, 11 (15.7%) received two doses and 53 (75.7%) received all three doses. Among the participants who received full vaccination i.e., 3 doses, 5 (7.1%) failed to develop protective immunity, i.e. they had anti-HBs titer <10 mIU/mL. 9 (12.8%) participants who received two doses and 17 (24.3%) participants who received only one dose failed to develop protective immunity. Conclusion: Nursing staff should have adequate protective immunity to HBV. Since two doses of vaccine did not completely protect them against HBV, a full vaccination schedule should be recommended for this group. Key Word: Hepatitis B vaccine, nursing staff, anti-HBs titer, protective immunity

INTRODUCTION Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is highly infectious and causes serious health problems worldwide. Nursing staff are at high risk for HBV infection because of particular exposure of mucus membranes and breached skin to blood.1-3 HBV-infected HCWs can transmit HBV infection to patients.4 Approximately 70% of HCWs in hyperendemic or intermediate endemic countries have been reported to have needle-stick injuries, with an average of two needle pricks a year.5-8 Risk of HBV infection is also related to the HBe antigen (Ag) status of the source person. Reports from India indicate that only 16-60% of HCWs have received complete HBV immunization. Nurses have a higher risk of HBV/HCV transmission and receive HBV vaccination less often than doctors.9,10 The practice of universal precautions, such as safe needle disposal, wearing gloves during phlebotomy and using goggles is suboptimal among HCWs in developing countries.11 In the present study we evaluated immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in nursing staff at a tertiary care hospital.

MATERIAL AND METHODS This prospective study was conducted to evaluate the status of HBV immunization among nursing staff. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. A total of 70 nursing staff were included in the study. After written consent, nursing staff received counseling and explanation on the objectives of the study by a qualified medical doctor.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Detailed personal history was taken using a standard questionnaire and 5 mL of blood sample was collected. The personal health information included demographic details of the HCWs regarding their age, sex, duration of employment, alcohol history, past history of blood donation or transfusion was taken. The status of HBV vaccination, exposure to blood and/or blood products, and the mode of HBV transmission were also recorded. Use of universal precautions in daily practice was also taken into account. Vaccination status was recorded. Vaccinated group was considered in subjects receiving 3 doses of HBV vaccination at 0, 1, and 6 months; whereas partially vaccinated group received either single or 2 doses at 0 and 1 month and unvaccinated group for those who had received no dose of HBV vaccination. Assessment of HBV infection: Blood samples were tested for hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) titre using a commercial kit (HBsAg ultra kit manufactured by BIOMERIEUX) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protective antibody titre levels equal or more than 10 mIU/mL for HBsAb were considered to be protective.12

RESULTS Out of the 70 nursing staff, majority 46 (65.7%) were between 21-30 years of age group followed by 18 (25.7%) between 31-40 years and 6 (8.6%) between 41-50 years. Of these 70 staff, 56 (80%) were female. All nursing staff had been vaccinated with Engerix-B recombinant plasma derived vaccine in the deltoid muscle. Of the 70 nursing staff studied, 6 (8.6%) received only one dose, 11 (15.7%) received two doses and 53 (75.7%) received all three doses. Among the participants who received full vaccination i.e., 3 doses, 5 (7.1%) failed to develop protective immunity, i.e. they had anti-HBs titer <10 mIU/mL. 9 (12.8%) participants who received two doses failed to develop protective immunity and 17 (24.3%) participants who received only one dose failed to develop protective immunity.

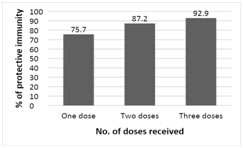

Figure 1: The percentage of protective immunity after different doses In individuals who received 3 doses the protective immunity did not reduce significantly after four years. After two doses of vaccination, there was significant deterioration in protective immunity after four years. Co-morbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, bronchial asthma) were not significantly associated with protective immunity to HBV following immunization. It was found that pregnancy had significantly impaired the protective immunity.

DISCUSSION HCWs form a major risk group for various blood-borne infections, including Hepatitis B virus infection. Vaccination is effective in protecting 90-95% adults.13 It was found that the practice of vaccination is not well-accepted. In the present study, Of the 70 nursing staff studied, 6 (8.6%) received only one dose, 11 (15.7%) received two doses and 53 (75.7%) received all three doses. A similar study done at New Delhi showed that 55.4% of HCWs were fully vaccinated against HBV.9 In a study by Kumar et al 42.2% of HCWs were fully vaccinated.14 In our study, among the participants who received full vaccination i.e., 3 doses, 5 (7.1%) failed to develop protective immunity, i.e. they had anti-HBs titer <10 mIU/mL. 9 (12.8%) participants who received two doses failed to develop protective immunity and 17 (24.3%) participants who received only one dose failed to develop protective immunity. This showed that almost 20% of the vaccinated HCWs were still at risk of acquiring HBV infection. The anti-HBs titer was significantly higher in the patients who had received vaccination within the previous four years. There is a gradual decline in the anti-HBs titer over the period of time in the vaccinated persons, so partially vaccinated individuals as well as a significant percentage of the fully vaccinated HCWs might have titers insufficient to protect them against HBV infection. Long-term studies in hyper-endemic areas indicate that immunological memory remains intact beyond 10 years after vaccination; thus initial vaccination offers protection against HBV infection even after anti-HBs declines below detectable levels.15,16 There is no evidence to show that healthy vaccinated individuals lose their immunity against HBV infection after anti-HBs titers decline to below 10 IU/mL. Sukriti et al stated that 20-50% of the vaccinees did not have protective anti-HBs levels (>10 IU/mL) after 5 and 10 years of vaccination, respectively.9 They recommended passive-active immunization for post-exposure prophylaxis after 5 years, with a booster dose after 10 years of initial HBV vaccination. Although there are no recommendations found to have the regular booster doses. Therefore, it is recommended that one should check anti-HBs titer regularly at a span of 5 years post HBV vaccination in the HCWs. As nursing staff are likely to contact with virally infected body fluids or blood, particularly those residing in countries of high and intermediate endemicity for HBV, they should receive vaccination at their initial entry to their respective training or professional practice. A booster dose should be recommended if anti-HBs titers are low.

CONCLUSION Nursing staff should have adequate protective immunity to HBV. Since two doses of vaccine did not completely protect them against HBV, a full vaccination schedule should be recommended for this group. The knowledge about vaccination, checking antibody titer regularly and screening for HBs antigen should be made compulsory for HCWs.

REFERENCES

|

|

Home

Home