|

Table of Content - Volume 18 Issue 1- April 2021

A study of association between chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies and clinical state of asthma in adult and paediatric patients

Vaishnavi Madavi1*, Renu Bharadwaj2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology, TNMCM & BYL Nair Ch. Hospital Mumbai, INDIA. 2Visiting Professor, Department of Microbiology, B.J. Government Medical College & Sassoon General Hospital Pune Maharashtra, INDIA. Email: devaki.vm@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Taking into consideration the growing interest in the role of C. pneumoniae in asthma and other cardiopulmonary diseases, this study was conducted to find out the role of C. pneumoniae in asthmatic patients by using serological methods. Aim and objective: To study the Association between Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies and clinical state of asthma in adult and paediatric patients. Material and methods: Present study was a prospective study carried out on patients presenting with characteristic symptoms of asthma or having medical history of asthma. Total 100 patients were selected as cases. A total of 50 age and sex matched patients were included as controls. The sera were tested for presence of anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM, anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG and anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA antibodies using commercially available kits (NovaTec Chlamydia pneumoniae ELISA). Results and discussion: In pediatric asthmatic patients (both acute and chronic together), antibodies present were IgG (23.3%), IgM (16.7%), IgG and IgA antibodies together (10%) and IgM and IgG antibodies together (3.3%). In adult asthmatic patients (both acute and chronic together),antibodies present were IgG (30%), IgG and IgA together (25.7%), IgM (14.3%) and IgM and IgG antibodies together (7.1%).

INTRODUCTION High prevalence of asthma and the obstructive pulmonary diseases in the general population has a major impact on the quality of human life. This has been the subject of numerous investigations in the last two decades. Many attempts were made to find out the cause of these diseases. Multiple hypotheses were put forth regarding the etiology of these diseases. Recently, infections by viruses and atypical bacteria have been blamed to play a role in such diseases.1 Chlamydia pneumoniae is a member of the Phylum Chlamydiae.2 The chlamydiae contain a diverse range of obligate intracellular bacteria occurring in amoebae, fish, reptiles, mammals and humans. More than 50% of adults in U.S and other countries show serologic evidences of past infection with C. Pneumoniae.3 Studies indicate that C. pneumoniae infection is worldwide in distribution.4 40-60% of adult human population across the world has been reported to be infected by C. pneumoniae.5 In temperate zone countries, C. pneumoniae has been implicated in community acquired respiratory tract infection in all ages, except under 5 years.6 In adults, 6-20% of community acquired pneumonia, 5-10% of bronchitis and sinusitis are caused by C. pneumoniae.3,6 4.5-25% of children have been affected by C. pneumoniae infection.7 Seroprevalence studies indicate that rate of C. pneumoniae infection is low in children below the age of 5, rises during school years and then infection persists throughout adulthood.8 This organism has a propensity to cause chronic infections and is often associated with ciliary dysfunction and epithelial damage in bronchial cells.3 Different techniques are available for the diagnosis of C. pneumoniae infection. These include isolation and identification of organism by using cell culture techniques, immunofluorescent assays like direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test and the molecular methods like PCR. Serological assays are used in the later weeks of the infection when antibodies are produced. The methods include commonly used assays like microimmunofluorescence (MIF) assay, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and compliment fixation test (CFT).8 ELISA is used to detect anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA, anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM and anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG antibodies. Clinical state of asthma is related with infections of respiratory infections. The detection of anti-Chlamydial IgM, IgG and IgA antibodies is important to diagnose the acute and chronic infections and it also helps to assess response to treatment and prognosis of patients. Present study was conducted to see the Association between Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies and clinical state of asthma in adult and paediatric patients. Aim and objective: To study the Association between Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies and clinical state of asthma in adult and paediatric patients

MATERIAL AND METHODS Present study was a prospective study carried out at a tertiary health care centre during period of January 2012 to December 2012. Study population was Individuals of all age groups (Total 100), attending the outpatient clinic and inpatient department of chest and TB and department of pediatrics, presenting with characteristic symptoms of asthma or having medical history of asthma and 50 controls. Inclusion criteria:

Acute asthma1, 2, 111 is defined as An abrupt or progressive worsening of shortness of breath, wheezing, chest tightness or cough of underling asthma and use of accessory muscles of respiration. It requires urgent treatment. Chronic asthma1 is defined as According to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines, duration of symptoms (days per week) such as breathlessness, cough, chest tightness or wheeze (or combination of these) requiring maintenance treatment to achieve partial and total control. Exclusion criteria:

Study was approved by ethical committee of the institute. A valid written consent was taken from the patients/ parents of ill children after explaining study to them. Total 100 patients were selected as cases. A total of 50 age and sex matched patients were included as controls. These were suffering from various diseases needing a surgical treatment. None of them had any cardiac or pulmonary disease. 5cc of blood in adult and 3cc of blood in pediatric patients was collected in a sterile plain vacutainer. These vacutainers were kept at room temperature for 30 minutes allowing the blood to clot. Sera were separated by centrifugation at 1800rpm for 30 minutes. The separated sera were collected in Eppendorf vials and stored at -200C (in a deep freezer) until further testing. Haemolyzed samples were not processed and repeat blood samples were requested and collected. The sera were tested for presence of anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM, anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG and anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA antibodies using commercially available kits (NovaTec Chlamydia pneumoniae ELISA). Data was entered in excel sheet. Comparison of anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies with asthma was done by applying Chi-square test and Fisher’s Z-test. p value < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

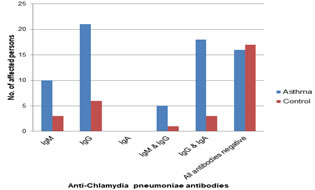

RESULTS Table 1 shows that, acute asthma is more common in the age group of 9-12 years (66.7%) while chronic asthma is more common in both the age group i.e.5-8 years (50%) and 9-12 years (50%). Table 2 shows that, acute asthma is more common in the age group of 51-60 years (32%) while chronic asthma is more common in the age group of 51-60 years (24.4%) and 61-70 years (24.4%). Fisher’s Z-test was applied for comparison of different antibodies in bronchial asthma with control. p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In pediatric patients, IgM, IgG, IgM and IgG together, IgG and IgA antibodies together, are statistically more significantly associated with asthmatic patients (p value < 0.05) when they are compared with the control patients. In Pediatric asthmatic patients it was found that IgM antibodies are more significantly associated with acute asthma than with chronic asthma, IgG antibodies are more significantly associated with chronic asthma than with acute asthma. The association of IgM and IgG antibodies together or IgG and IgA antibodies together with asthma was found not to be statistically significant. (table 3) In adult patients IgM, IgG, IgM and IgG together, IgG and IgA together are statistically more significantly associated with asthmatic patients (p value < 0.05) when they are compared with the control patients In adult patients IgM, IgG, IgM and IgG together, IgG and IgA together are statistically more significantly associated with asthmatic patients (p value < 0.05) when they are compared with the control patients. In adult asthmatic patients it was found that IgM antibodies are more significantly associated with acute asthma than with chronic asthma, IgG antibodies are more significantly associated with chronic asthma than with acute asthma. IgM and IgG antibodies together are more significantly associated with acute asthma than with chronic asthma. IgG and IgA antibodies together are more significantly associated with chronic asthma than with acute asthma. (fig 1)

Table 1: Distribution of pediatric asthmatic patients according to their age and clinical state of asthma (acute/chronic)

Table 2: Distribution of adult asthmatic patients according to their age and clinical state of asthma (acute/chronic)

Table 3: Comparison of different antibodies in pediatric asthmatic patients with control

Figure 1: Comparison of different antibodies in adult asthmatic patients with control

DISCUSSION In our study, Pediatric asthmatic patient in both clinical stages (acute and chronic), majority of the patients 7/30 (23.3%) had IgG antibodies. 5/30 (16.7%) patients had IgM antibodies. 3/30 (10%) patients had IgG and IgA antibodies together. Only a single patient had (3.3%) IgM and IgG antibodies together. The remaining patients 14/30 (46.7%) did not have any kind of antibodies. Considering the controls, very few patients 2/20 (10%) had either IgM or IgG antibodies in very low titers. Only a single patient (5%) had IgG and IgA together. 15/20 (75%) did not have anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies. These values are statistically significant by applying Fisher’s Z-test (p-value < 0.05). Youseef et al.9 showed IgG 30%, IgM 10.83% and IgG and IgA 5%. These results correlate with our study. The pediatric patients suffering from acute asthma (12/30 (40%)), 4/12 (33.3%) had IgM in high titers and there was only a single patient who had IgM and IgG together (8.3%) in low titers. These indicate that they are in the very early stage of C. pneumoniae disease and are going to develop further. Considering the pediatric patients with chronic asthma majority of the patients had IgG followed by IgG and IgA together in their blood. 38.9% had IgG and 16.7% patients had IgG and IgA together which indicates these patients are in chronic or persistent state of infection. Wazir et al.10 reported a percentage of 40.7 and Annagur et al.11 reported a percentage of 40.5, which correlate well with our study (for IgG). Normann et al.12 using MIF reported a quite low percentage of 13.7 for IgG. Kopriva et al.13 (8%) and Normann et al.12 (7.14%) reported a quite low percentage of IgG and IgA together than our study. This was may be due to different geographical distribution. Our results showed that, in adult asthmatic (acute and chronic) 21/70 (30%) patients had IgG while 18/70 (25.7%) patients had IgG and IgA together. 10/70 (14.3%) had IgM antibodies. Very few patients 5/70 (7.1%) had IgM and IgG antibodies together. The remaining patients 16/70 (22.9%) had no anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies. In the present study, majority of the patients had IgG (30%). However, Hahn et al.14 reported a percentage of 26.7 for IgG. In present study 25.7% had IgG and IgA antibodies together and 7.1% patients had IgM and IgG antibodies together. Agarwal et al.15 mentioned 23.3% for IgG and IgA together and 3.3% for IgM and IgG together which correlates well with our study. In present study, we found 14.3% patients had IgM. This finding correlate well with Agarwal et al.15 who reported 15% of IgM. As far as patients of clinically diagnosed acute asthma were considered, 7/25 (28%) had IgM in high titers which may be due to very acute stage of asthma or acute exacerbation of asthma. Following this the next major lot of patients is those having both IgM and IgG antibodies together 5/25 (20%). These patients might be into earlier stages of the acute disease or the patients in reinfections. Only a couple of patients 2/25 (8%) had IgG only or IgG and IgA together. These patients might be in a single stage of earlier weeks of the acute disease. In this study considering the titers of all types of antibodies we found that some patients in both clinical stages of asthma (acute and chronic) did not produce any anti-Chlamydia antibodies. Their number varied from 15.6-36% of total. The patients with clinically diagnosed acute asthma might be in the very early stages of the disease where early manifestations are seen but the antibodies have yet to appear. Similarly in patients with clinically diagnosed chronic asthma, the disease might be due to a non-infectious atopic cause or the patients might be elderly with producing a weak immune response (which is not detected by the diagnostic assay). Considering the adult acute asthmatic patients IgM antibody was the predominant antibody in them. We found this antibody in 28% of patients. Agarwal et al.7 mentioned a percent of 15 of the patients. This percentage is quite low because they have not differentiated their patients in acute and chronic asthma. In the present study IgG antibodies were detected in patients (2/25) in early stages of acute asthma. Variable results have been reported by many workers: Agarwal et al.15 (80%), Torshizi et al. (16) (81%), Wark et al.17 (18.5%), Hahn et al.14 (26.7%). The gross differences in results of these workers is due to two reasons, some workers (Torshizi et al.16 and Wark et al.17 have selected only acute cases of adult asthma, while others have selected asthmatic patients as a whole, without differentiating them as acute or chronic. In addition some have used genus specific ELISA and others have used species specific ELISA. So that the values may not be comparable.

CONCLUSION If acute C. pneumoniae infection occurring in the childhood is detected early and treated effectively at that stage only; it can prevent the patient developing a chronic asthmatic status in his future

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home `

`